—–

Since their inception, movies and television have glamorized the life of a physician, often intertwining personal stories of said physicians with the heroic acts they perform and the inherent braininess required therein.

This is only a mild reality.

—–

—–

Sure, physicians are by-and-large smarter than the average bear, but it is our tireless work ethic, attention to detail, and self-loathing which provides us the ability to make such a significant impact in the lives of our patients.

There is little glitz, even less glamour, and only the occasional heroic act in the life of a physician. But the combination of these traits keeps many of us going back to work every day.

No. I mean EVERY day. As in… working EVERY. SINGLE. DAY.

In case you can’t tell I’m currently smack dab in the middle of my second year of Residency (aka PGY-2)… a time I have affectionately termed, “The Rise of Magneto.”

—–

—–

Though some more recent medical dramas have included the lives of Residents, this middle ground in the hierarchy of medicine is poorly understood and recognized.

After completing medical school, newly-minted physicians in the US must complete a Residency before becoming a physician capable of practicing on their own.

In the US, simply completing medical school is not sufficient to become a physician; no hospitals or physician groups will hire you; no insurance will reimburse you.

—–

—–

Instead, you must prove your worth, knowledge, and skills by completing a Residency in the specialty of your choice.

Alas, the general public is not fully aware of this transitional stage in the professional life of a physician. There is either “you are a doctor” or “you are not a doctor”.

And if the patient is sitting in a gown, on an exam table or on a hospital gurney, while asking for medical help and you identify yourself as their physician, “you are a doctor.”

Which, in fact, you are.

Confused yet?

Well, I am too.

Because now that I’m half-way through my Residency, I am starting to find myself straddling the line between being a naive Intern and a full-fledged Attending.

—–

—–

The major reason Residencies exist in the US is due to the wide swath of information and skills needing to be honed in order to provide adequate medical care in the 21st century (and the 20th century before it.)

The sheer breadth of knowledge acquired during these training programs is paramount to fully understanding the capabilities, pit-falls, and intricacies of the human body.

It also introduces physicians to the longitudinal aspects of caring for patients and their families.

—–

—–

One night while I was an Intern (PGY-1), I responded to an overhead page from the Emergency room; my assistance was requested in the care of a critically ill patient.

Not exactly “my” assistance per se, but by being the Intern on-call, I was part of the team responding to patients who have such a severe infection as to be called “Septic“.

The woman was non-responsive, cool to the touch, and seemingly every square centimeter of her body was swollen with fluid.

Her vital signs on the monitor were tenuous. A quick scan of her body revealed a tube protruding from her pelvis, most likely a surgically placed catheter to drain urine from her bladder.

The daughter sat at the bedside, quickly describing the course of actions she believed could have led to the current predicament.

Despite her seated position at the bedside, her fear was palpable.

I thanked her for the explanation and informed her we would need to pursue aggressive measures to save her mother’s life. Without hesitation, she consented.

Over the next several days, her mother remained unresponsive in the Intensive Care Unit, her life supported by machines to keep her lungs delivering oxygen to her swollen body; medications kept her heart pumping that same oxygen to every fragile cell.

—–

—–

But one day shortly thereafter, I arrived in the ICU and the mother was no longer in the room.

The bed was barren, immaculately cleaned, and prepared for the next critically ill patient.

She had died overnight, her body unable to sustain life despite the most aggressive medical interventions, all while I attempted to regain my cellular integrity through several hours of sleep in my own poorly-cared-for apartment.

—–

—–

Six months later, I was working in the office of an Oncologist (a doctor who treats patients with cancer) preparing to see his next patient. While thumbing through her chart, he described the course of events leading her to seek his care.

When we entered the room, I saw a familiar face. The daughter of the non-responsive woman I just described. She smiled and greeted me, though I instantaneously recognized her palpable fear.

The Oncologist was surprised and said, “you two know each other?”

I responded, “yes, I cared for her mother.”

—–

There were no heroic acts which changed the outcome of the mother’s life. Unfortunately, there were no heroic acts to perform for the daughter either.

—–

In our current “illness-based” medical system, which more handsomely rewards interventions while people are ill, even Family Medicine docs like myself tend to more commonly encounter patients when they are in need, rather than when they are well.

{This is more a by-product of when people tend to seek out care, rather than a desire on most physicians part, as Family Medicine is predicated on prevention of illness.}

And sometimes the wellness and illness intersect.

—–

—–

Having completed two months of Obstetrics and Gynecology during my intern year, as a PGY-2 I have become “eligible” to work 24-hour shifts on the Obstetrics service.

The Rise of Magneto, indeed.

{By eligible, I mean the cap on my consecutive hours able to be worked is now 24… And I am assigned to work said shifts based on my availability. Which is truly, whenever. But that is Residency. So be it.}

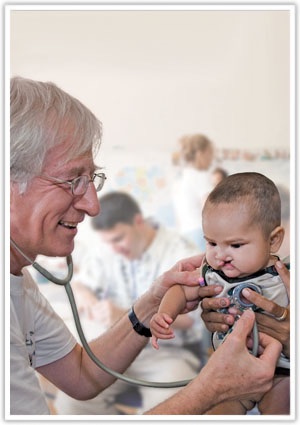

Within the first hour of working my first OB-24, I delivered the baby of a woman I had never met, which is common on the Labor & Delivery service.

After ascertaining the baby’s general health and wellness while identifying the absence of suturing opportunities in the woman’s vaginal canal, I calmly congratulated her, welcomed her son to the world, and exited the room to tend to another pregnant woman.

—–

—–

One week later I was working in the Pediatric Emergency Department, my latest assignment as a PGY-2, when my eyes were drawn to a patient’s Chief Complaint on the Patient Tracking Board.

It read “fever, decreased PO intake”. I scanned over to the patient’s age and read, “7 days.”

On my first night in the Pediatric ED I had seen another 7-day-old with fever and decreased PO (oral) intake. I ended up performing a lumbar puncture that night on that child due to a concern for meningitis.

Thankfully, the test results came back showing that the child did not have meningitis. It recovered quickly and was home within two days.

—–

—–

But that experience had quickly alerted me to the need to act quickly and decisively in order to prevent a dire outcome.

So I clicked my name next to this latest 7-day-old child and quickly proceeded to the patient room to evaluate him.

When I opened the door and introduced myself, the mother and I instantaneously recognized each other. She was gently rocking the boy I had delivered only 7 days previously.

—–

—–

I had only a week before assisted his exit from his mother’s womb. I assured his mother we would care for him and made my way back to the area where an Attending physician was awaiting my assessment and plan.

While I alerted my Attending to the intimate relationship I possessed with this child and his mother, a few of the other Residents and Attendings happened to overhear the predicament.

They all began to listen in as I outlined my plan to perform a Lumbar puncture to assure he was not rapidly deteriorating at the hands of a bacterial foe.

My Attending agreed, looked at me intently, all the while recognizing my whole-hearted investment in this patient.

—–

—–

There are few instances in medicine as intimate as the delivery as a child, and to have that same child fall ill and somehow end up back within your care in a completely different hospital on a completely different medical service only a few days later, is the essence Family Medicine.

We can be seemingly ubiquitous.

Thankfully, the young boy, only a week into his life, tolerated the Lumbar puncture; his cerebrospinal fluid was absent of life-eradicating bacteria or virus; he was sleeping comfortably in his own crib again within two days.

—–

—–

The transition from “medically knowledgeable but clinically deficient Intern” to “clinically seasoned and seemingly knowledgeable Senior Resident” is one fraught with pitfalls: sleep deprivation, anxiety-producing clinical scenarios, life-and-death struggles, and glaring holes in medical knowledge.

But at the moment of greatest despair, when the chips are down, the night can’t end, the day can’t come soon enough, and the struggle to become a good physician seems out-of-reach, the Intern becomes a Senior Resident.

And reflects back on the do-or-die nights, the life-and-death days, the thankful patients, the grateful families, the new-born babies first squeel, and the meaningful and life-long relationships created in the cauldron of uncertainty…

… bringing on The Rise from Intern to Senior Resident.

In my case, The Rise of Magneto.

3 comments