Death Becomes Us…

—–

If everything goes as imagined, my final breaths will be exhaled several decades from now as I look out upon the Atlantic Ocean.

Watching the waves crash upon the shore, I will be alone. By choice. Not wishing anyone I love to see me as a dying corpse, gasping for my last breaths. Hopefully the tide will come crashing in, and, in its return to the ocean, take my body too.

I will have said goodbye to my surviving friends and family while still upright and mobile. Exchanging long embraces, we will depart each others presence to live another day.

My wife, ever accustomed to my eccentric nature, will have laughed, and cried, when the day came for me to leave her, just as I had promised her long before. We will have sat beside our parents, friends, perhaps one of our children, and other loved ones while they succumbed to life’s final crescendo. They not wanting to leave us, and we, not wanting to leave them.

But, Death Becomes Us.

—-

—–

The first time I crushed a man’s ribcage, I was furiously trying to save his lifeless body. As a third year medical student in the ICU, I was tasked with performing chest compressions on a corpse who had, in written certitude, asked for all measures be performed to save his life.

As I felt the brittle bones disintegrate beneath my force, I continued in rhythmic fashion, counting under my breath, and wondering to myself:

“Did anyone see my millisecond of hesitation after the first rib snapped?”

—–

—–

He did not survive. Despite medical science, unwavering will power, the love of everyone in his life, and perhaps a god somewhere in our cosmos, he died like everyone else who had ever lived before him.

He died. Just like I will. Just like you will.

In the three years since that time, I have been present for the deaths of innumerable people. I have lost count.

I don’t believe the number is actually any more than 50, but that’s enough for me to recognize I will die too.

—–

—–

As a physician, I have had the responsibility to pronounce the death of a once-living person. The first time I was called upon to do so, I walked to the patient’s room, and therein, found an elderly woman sitting beside her husband’s dead body, surrounded by her adult children.

The body was already in rigor mortis, laying in the bed, with a crisp white sheet covering the torso, the arms extended beside the chest, and the eyes and mouth closed; forever.

I politely introduced myself to the family, reached my arm out to hold the hand of the widow, and clasped it in my hands for a moment.

I informed the family I would need a moment to examine the body, but they were welcome to stay at the bedside. The widow rose from her seat, looked at her dead husband’s body, and asked to be excused. She stepped behind the room-dividing curtain; one of her daughters joined her.

—–

—–

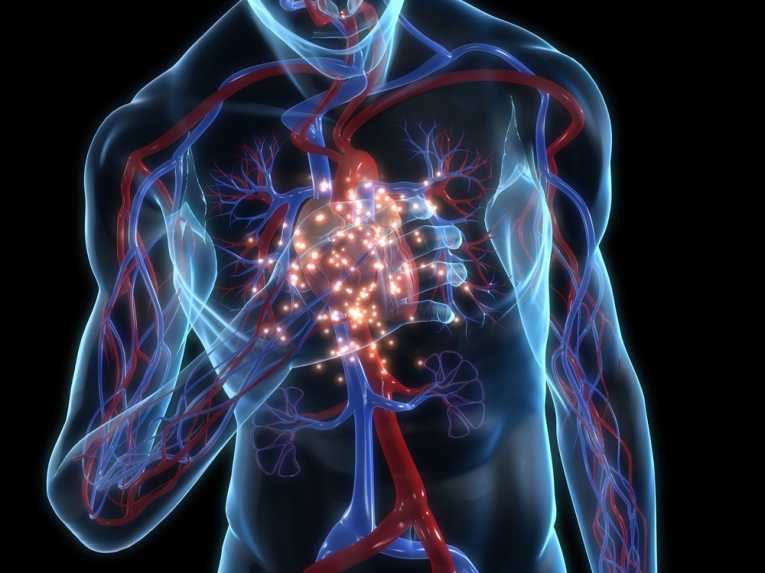

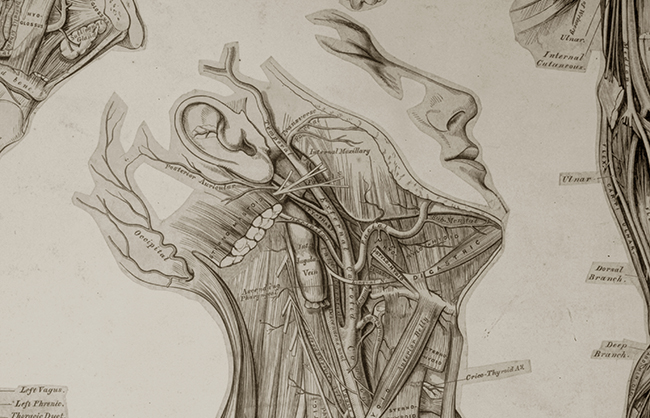

The diaphragm of my stethoscope was placed over the Aortic region of the chest. My right hand made its way to the left wrist; the pads of my first and second fingers palpated for the radial pulse.

I closed my eyes and listened for a heart beat I knew I wouldn’t find. Simultaneously, my fingers pressed gently, trying to feel a pulse I knew wasn’t there. I moved my stethoscope around on the chest, never once hearing a heart beat or breath.

For completeness, I firmly pressed on the nail bed of a finger, trying to elicit the jerking motion a live man would provide. There was no response. I withdrew my penlight from my left chest pocket, spread the eyelids, and shone the light directly on the pupils. They were fixed and dilated; they did not react at all. I gently released the eyelids.

—-

—–

I respectfully informed the family my examination was complete and provided my condolences.

The widow appeared again and sat back down beside her lost love. I exited the room and proceeded to file my pronouncement of death. I entered a note in the now dead patient’s chart. I called the physician of record to inform he or she of the passing.

In the subsequent months, I have made similar appearances at the bedside, sometimes finding grieving family, other times a vacant room. Each time, the pronouncement was the same.

The time I spent in the ICU as a medical student was easily eclipsed by the four weeks I spent therein as a Resident Physician. Death was only an embolus, cardiac dysarrhythmia, antibiotic-overpowering infection, or apneic respiration away for each person. And on numerous occasions, those life-ending insults occurred simultaneously.

—–

—–

The four weeks of care I provided in the ICU was tempered by the realization that some of it would be futile. A concerned son, seated at the bedside of his father, stopped me one afternoon and asked, “Excuse me doctor, what does it mean if the brain waves are prolonged?” I took a hard look at his father, a man I had never met, who ended up as my patient that morning after a massive heart attack deprived his brain of its needed oxygen, and then looked back at the son, himself a grown man older than I, and took a deep breath.

Nothing I could explain would bring his father back. Nothing we could do in the ICU would change his outcome. We are here for a finite amount of time. And in essence, I explained to a son that his father’s time had come.

I did not feel relieved that I could near-effortlessly explain the basic inner working of the heart, brain, and circulatory system to this man; all of which I had acquired after countless hours of study and dedication. Instead, I felt emboldened to never have someone utter the same nuanced phrases to my own son.

—–

—–

Similar occurrences happened on a daily basis for four weeks. For the fortunate, the family would withdraw the aggressive machinations, which, if prolonged, would have provided a miniscule chance of survival. For the unfortunate, their own wishes (and sometimes their family’s) had been so misguided as to result in aggressive and invasive procedures, which, if successful, would provide only a miniscule chance of survival.

Yet, I know the final minutes, hours, and days provided to the loving members of those patients’ families was beyond worthwhile. To them. To the patient. And to me.

—–