Trauma E

—–

My final clerkship of medical school was a Trauma Surgery rotation in Columbus, OH. As a “Level 1” Trauma Center, I was certain to see all sorts of medical traumas. From horrific car accidents, penetrating stab wounds and life-ending gun shots, to suicide attempts, both successful and unsuccessful, sporting injuries, and the aftermath of violent beatings.

Rather than leaving Columbus and heading to Worcester, MA for a radiology clerkship where I could stay with some of my dearest friends and put in 4 hour days, I decided to stick around Columbus, have a 4:30A wake-up call, 9P bed-time, and expose myself to an aspect of medicine that I was unlikely to encounter in my future practice as a Family Medicine physician.

—–

—–

And that is exactly what happened, as the four weeks I was on the Trauma Service was the busiest month in the history of the hospital.

Anyone who knows me well, or has spoken to me about my experiences in medical school, knows that I typically don’t care for the attitudes of surgeons. While it is a profession that requires its practitioners to be exquisitely skilled, the god-like aura that typifies a surgeon, especially towards students, is enraging. (And completely unnecessary.)

—–

—–

But despite this behavior, I wanted to be a part of the care of patients who present to the hospital after a traumatic accident… Or as I was resoundingly corrected by one of the trauma surgeons when speaking of a motor vehicle accident (MVA), “it was a motor vehicle collision, as we don’t really know if it was an accident.” Thanks a**hole.

On the student’s first day of any clerkship, the other students, residents, and physicians will ask about the new student’s future career aspirations. This is done to determine the level of shit the student should be given over the course of the next four weeks.

If the student is interested in becoming a member of that medical profession, they will be held to a higher standard, given more grunt work, asked to work longer hours, and expected to know a ton more than someone who’s professional aspirations are 180 degrees different.

—–

—–

Thus I found myself having the following exchange with the Chief Resident two minutes into the rotation: “So what year are you?”

Me: “I’m a fourth year. And this is my last rotation of medical school.”

CR: “Are you going into Surgery?”

Me: “No. Family Medicine.”

CR: “What the hell are you doing here?”

Despite this inauspicious beginning to our medical relationship, the Chief Resident ended up being a terrific teacher, physician, and all-around good guy.

His “Surgeon’s Aura” was usually absent. In regards to surgeons, this guy was the proverbial medical zebra that you are taught to stop looking for… But in his defense, it’s simply not common place to see a 4th year medical student sign up for a grueling clerkship as their last hurrah of medical school. Typically, it’s something like… Radiology.

—–

—–

Several of the Family Medicine residents with whom I worked previously had suggested the clerkship, so I went into it with a positive attitude. I figured, if anything, that I could bring some humanity into the trauma bay… as by-in-large, the trauma bay is one of the least “human” experiences in medicine.

Upon a patient’s arrival, multiple people are poking, prodding, screaming, shouting, slicing, sticking, cutting, and tearing… at the life and limb of this latest entrant to the trauma bay.

—–

—–

Depending on their level of consciousness, the patient may or may not be screaming and shouting. If they are unconscious, the distractions are seemingly less, but the situation is quite significantly more dire. I preferred the screaming and shouting patients because it meant they were more likely to survive.

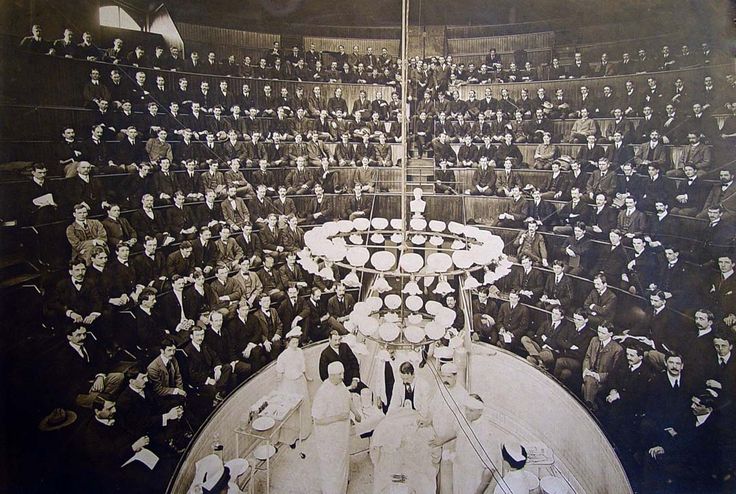

But the surgeons, they prefer the deafening silence of the patient because the stakes are raised, the opportunity to transport them to the surgical theater more likely, and their god-like skills are soon to be exercised.

—–

—–

Over the course of four weeks, I cut off my fair share of pants and underwear, placed innumerable Foley catheters [a tube into the urethra of both men and women], and stuck a gloved and lubed finger into the rectum of more people than I care to admit… but that was all done so that I could say to the patient, “We are going to take care of you”… and to mean it.

In a nutshell, that is the humanity that is absent from the trauma bay. It is a rarity for someone to ask for a patient’s name; no one states a desire to care for you; no one even thinks of doing either of those until the patient is either on the way to the CT scanner, surgical theater, or morgue.

—–

—–

But one of the clinical psychologists I encountered during a previous rotation had mentioned a quick anecdote that stuck with me. His father had recently been in an accident and while laying on his back, with numerous people he didn’t know poking and prodding him, he had some of the terrifying fear, anxiety, and uncertainty removed by someone who immediately stated upon his arrival in the trauma bay, “We are going to take care of you.”

—–

—–

I carried that anecdote with me each time another Trauma was called over the hospital’s intercom system.

I think this kind of humanity becomes absent as a defense mechanism from the care-providers.

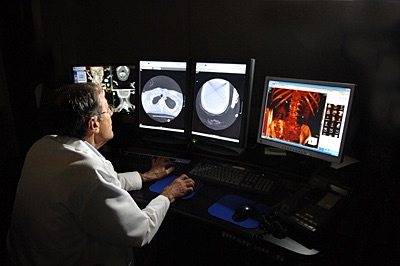

Because when someone is wheeled into the trauma bay, their next destination may be the CT scanner to determine the extent of their injury.

Or the surgical theater as a last-ditch effort to save their nearly life-less body.

Perhaps the morgue, because the extent of their injury was too great for even a god to cure.

—–

—–

And when the outcome could be either of the last two, I would imagine it becomes difficult to not simply view each new patient as a body on whom your craft can be practiced… until your craft has provided a life-sustaining result.

Then, after all is said and done, and the patient is alert and speaking to you, their worst day behind them, only then can you entertain the idea of knowing their name; Or offering to care about/for them. Until then, they are simply Trauma [A, B, C, D, etc].

—–

—–

But what if that next day never comes.

And in their final moments no one is calling their name.

No one is telling them that they care about them.

Then what?

—–