—-

After hurriedly caring for two newly admitted patients, while receiving pages from nurses about the other patients already admitted to my service, I took a moment to “run my list.”

At 2AM on a Thursday morning, my brain required a succinct “to do” checklist to assure nothing of importance had been forgotten. Fortunately, I simultaneously happened upon my senior resident, Jacob.

He calmly asked how things were going, having left me hours before, in a trial by fire, to go about the business of running an in-patient service on Nightcall. Not that he had abandoned me, but rather, he had given me the reigns of our service and asked that I not make any decisions which caused him to question my ability as a soon-to-be second year resident.

—–

—–

I collected my thoughts and began rattling off updates, allowing both of us to check off a multitude of things on our list. As I made my way to the middle of our list, I let out a quick a deep sigh.

He gave me a quizzical look, to which I responded, “I need to go check on Ms. Smith’s EKG. I was supposed to do that two hours ago.”

—–

Jacob and I had been paired to work together for these two weeks since our schedule for the year had been published months earlier. It was likely intentional, as Jacob had been identified as a leader within our program, and thus someone from whom I could learn to become a solid second year resident.

Though several years my junior in age, I respected Jacob’s work ethic and pride in our residency. Despite the long hours, occasionally ungrateful patients, and stress of balancing work and a family life, he kept a positive attitude and welcoming countenance. I could easily imagine him becoming a Chief Resident, one of the designated leaders of our program who toiled in an effort to provide stability in a world of chaos.

—–

My response prompted his characteristic comforting Arkansas twang, “Oh, don’t worry, Magneto. Ms. Smith is just fine.”

—–

—–

As a part of friendships, work relationships, and familial bonding, nicknames are a nearly ubiquitous part of life. Having been given a multitude throughout my years, I quickly realized Jacob had provided me the latest in a long line. But unlike most of them, which were derivations of my first or last name, and typically of little creativity, “Magneto” provided me a cache not previously recognized.

I let out a quiet chuckle as Jacob informed me he had wandered up to Ms. Smith’s room at midnight, the time I had told him an EKG would be performed to determine if her pacemaker had been deactivated, allowing her to pass into death comfortably. Once there, he learned of my own creativity, which christened the birth of Magneto.

—–

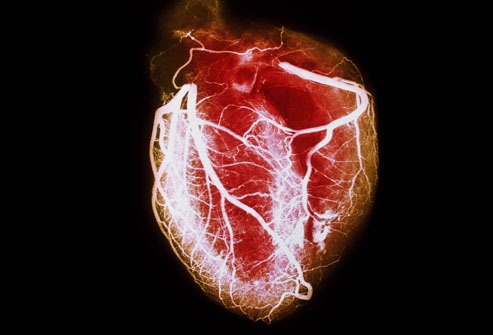

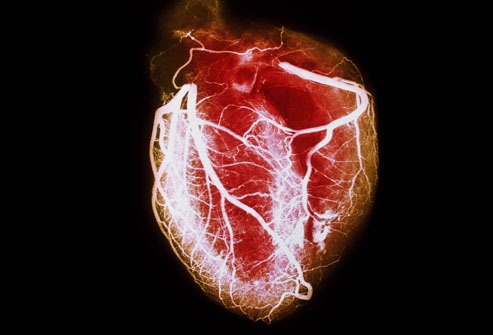

I first met Ms. Smith three weeks earlier, when I was working during the day as one of the interns on our in-patient service, Clin Med. At that time, Ms. Smith was struggling with advanced heart disease, a quartet of pathologies which I termed the “Unholy Alliance”; her heart provided her four diagnoses, which together carried a high level of morbidity and mortality: congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, and pulmonary hypertension.

Each of these diagnoses were intimately intertwined with the others, but I had yet to see any one person carry all four. During our initial encounter, Ms. Smith was easily conversive, despite her need for supplemental oxygen, and seemed ready to battle her disease and proceed well beyond her 63 years of life. On that day, she was flanked by one of her adult sons who reflected her success as a mother.

—–

—–

The night I earned my nickname, Ms. Smith was flanked by that same son, as well as her two adult daughters, several grandchildren, and a couple friends. They wished to be present in her final moments.

Between these two days, Ms. Smith had a brief, but meaningful improvement in her clinical status, allowing her to return home. But her heart quickly worsened and she ended up admitted to our service again, this time in more dire circumstances. It was immediately recognized that her final days were upon her and the one daughter who did not live in Columbus was summoned from California.

—–

—–

The final daughter’s arrival from California harkened a transition in care for Ms. Smith. She had made it known if she were to have a decompensation in her status, she would not want to be maintained indefinitely.

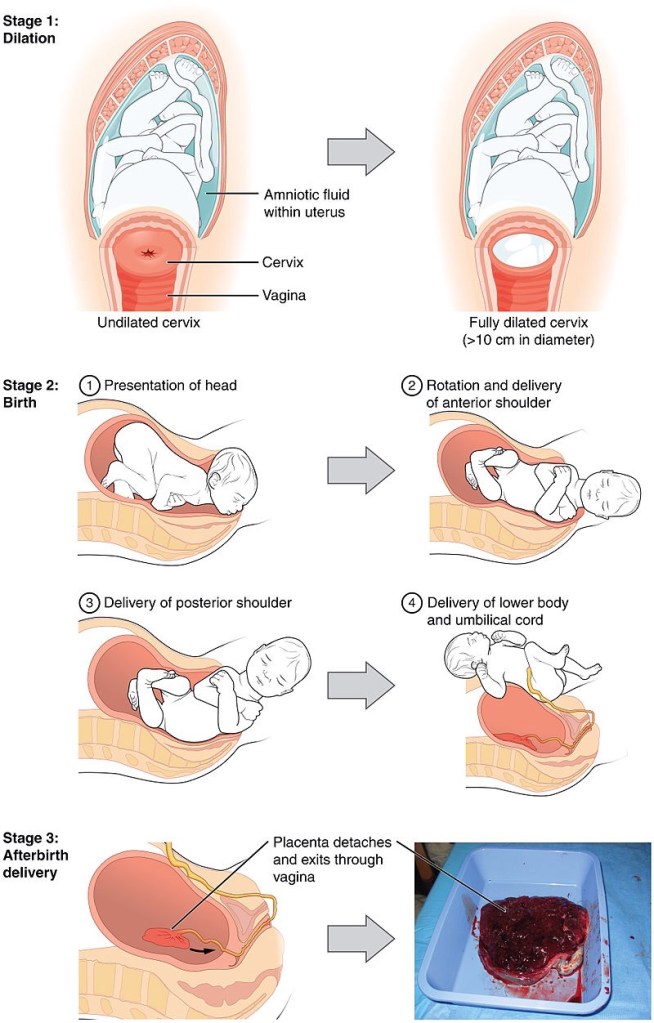

So while her mental status waned as a result of her poorly functioning heart, we provided her some medication to prevent it from going haywire, and more importantly, did not deactivate the pacemaker embedded in her chest. Her heart kept pumping despite the malignant nature it now carried.

When the daughter arrived earlier in the day, a decision was made to stop the medications and turn off the pacemaker, allowing Ms. Smith a nearly painless transition into death.

—–

—–

But when I arrived to work that evening, I was notified Ms. Smith’s pacemaker was still quite functional. The nurse paged me, reporting she had waved a magnet over Ms. Smith’s chest, performed an EKG to determine if her heart was still receiving the electrical impulses from the pacemaker, and found the characteristic pacemaker spikes on the EKG print out.

Only five minutes earlier, I was informed our Clin Med service would be directly admitting two patients; these two individuals would not be coming up from the Emergency Department, where an initial assessment had been completed, but rather were being either transferred from an outside hospital or being sent in from home by one of our colleagues.

This would require assessing the patients while they were already on the floor being cared for and simultaneously providing orders by which the nurses could care for them.

Dealing with one of these would be a trial in and of itself, but dealing with two simultaneously, while responding to pages about other patients on our service, would be quite a task. Jacob asked if I could handle it, to which I responded in the affirmative.

—–

The lone impedance I saw was Ms. Smith’s pacemaker. So I hurried up to the 6th floor, walked into her room, greeted her family, and confirmed I would be deactivating her pacemaker. They thanked me for our team’s care and focused their attention on their dying mother.

I excused myself for a moment, proceeded to the nurses station, rifled through a drawer beneath a bay of computers showing the electrical activity of every heart on the 6th floor, and grabbed a large, doughnut-shaped magnet, measuring 8cm in diameter.

—–

—–

Having been informed the nurse had attempted to deactivate it earlier and realizing the two direct admits were awaiting my care, my eyes began searching the nurses station for something I could use to secure the heavy magnet to Ms. Smith’s chest.

I found a strap with which I felt I could secure the magnet and walked back into Ms. Smith’s room. I greeted her family again, proceeded to her bedside, and lowered the gown from her left shoulder.

I intertwined the strap in the middle of the doughnut-shaped magnet and secured it around her shoulder, resting it snuggly against her upper left chest wall. I raised the gown back over her shoulder, informed her family I would return in a few hours to check on her, and proceeded from the room.

—–

After leaving Ms. Smith’s room, I found her nurse, asked her to perform an EKG at midnight, and informed her I would return shortly thereafter to assess Ms. Smith.

When Jacob christened me “Magneto”, it was two hours after I had planned to see Ms. Smith again. He had made his way to the 6th floor at midnight to check on Ms. Smith’s heart.

He informed me the EKG had, in fact, shown the pacemaker to have been deactivated, as I (and Ms. Smith) had wished. But deactivating her pacemaker was not like pulling the batteries from the back of a remote control, leaving her lifeless. It had simply removed the support needed to keep her heart beating more than 60 beats per minute, the lower level of “normal”.

—–

—–

Jacob relayed she was still alive, with a slowly beating heart, when he had gone to see her. We proceeded to run the rest of the list, I informing him of the status of our two directly admitted patients, and he of Ms. Smith imminent demise.

I left him and grabbed the elevator to the 6th floor. I slowly walked towards Ms. Smith’s room, the lights in the hallway dimmed appropriately for the time of night.

I knocked on the door, entered, and found her family members still gathered at her bedside, though overtaken with fatigue. They had made her room a makeshift resting place, blankets on the ground, tired bodies resting amongst each other, each of them soundly asleep.

And there was Ms. Smith, laying peacefully in her bed, continuing to have slow, agonal breathing, her heart surely winding down.

—-

As I quietly left the room, careful to not disturb her children and grandchildren, I took a deep breath and let out a sigh of relief.

I strolled through the darkened hallway, making my way towards the nurses’ station, but ran into her nurse before reaching my destination. She was on her way to assess Ms. Smith herself.

I informed her of my findings and asked her to keep me updated.

Five minutes later, I received a call from the nurse stating she entered the room, found Ms. Smith’s agonal breathing to have ceased, and was unable to feel a pulse. She had died.

—–

—–

I returned to her room some time later, having made another round through the Intensive Care Unit to assess the health, or lack there of, of the patients who were there. Her family was all awake, having been alerted to her passing, and profusely thanked me for our team’s care.

They thanked me by name and title, but were not aware of The Birth of Magneto.

39.961176

-82.998794