doctor

From Here to the Sea

We had been driving for quite some time, our trip dotted with several detours, by the time we arrived at the final checkpoint. As we came to a stop, there were hundreds of people lining the road, the result of the clearly demarcated “point of no further progress”, which necessitated them leaving their vehicles if they wished to investigate further.

I had expected to find some sort of barrier to prevent further vehicular transport, as Joseph had earlier remarked there would come a place where security would be heavy.

As we approached the checkpoint, even from my seat in the back of the SUV, I could see there was only a small security station with an uniformed officer. He was flanked by an elderly gentleman who sat in a small folding chair holding a thin rope across the road. In retrospect, it would be an inaccurate characterization to call it a rope; instead, it was more like a cord.

Certainly, if we had needed, we could have carried through the checkpoint unabated, likely causing only a slight rope burn to the old man’s hands as it was torn from his grasp. I doubt there would even be a thread on the bumper.

If we had decided to forgo the minor annoyance of stopping at this point, the security officer would have needed to make a quick decision: either climb into his vehicle and begin pursuit, which probably would have caused hundreds more to climb back into their vehicles in an attempt to evade the blistering sun and proceed past the check point; or stood guard, calling for back-up, and awaiting our return at some point, knowing the road ahead only went from here to the sea.

Instead, the portly gentleman we had picked up at the last stop jumped out of the back of the SUV, where he had been napping since we departed Rameswaram. He had joined us at the medical clinic for our trip to the sea for this exact moment.

I had not caught his name when he was introduced, even though I had been asked to palpate the abdominal hernia protruding from his large belly when we met some earlier. Later, I would come to discover he was to return from Rameswaram to Madurai with us that evening in order for him to undergo a surgical repair the following day.

Joseph, who also had joined us at the medical clinic and was in charge of the Rameswaram Trust, remarked that this man had some connections with the police and would have some words with the security officer standing post at the check point.

He returned a few moments later, climbed into the back of the SUV again, and the elderly man dropped the cord separating us from the continuation of our journey. We slowly rolled through the security checkpoint to the amazement, perturbation, and perhaps disgust of those we passed by.

The road from here to the sea had been finished months ago, Joseph informed me, but it had yet to be christened by the government, an act set for the following week, which necessitated the security checkpoint. There had previously been only sand covering the narrow strip of land separating the Bay of Bengal from the Indian Ocean until that time.

It had been laid down as a means for tourists to safely proceed to a point where they might find what remained along its path: the remnants of a town destroyed by a cyclone over 50 years earlier. Joseph grimly told me how the cyclone had ravaged the area, resulting in more deaths than he cared to recall. Many people had tried to escape by train or finding cover in the church or school.

When I looked closely, I could see a few railroad ties left visible as we continued along the road; I didn’t need Joseph to describe the scene that must have occurred that day. I could imagine the terror.

The opposite side of the road was pock-marked with destruction. It was barely evident that a congregation had ever met in the structure I was told had been the cathedral. Now sand-blasted and with no signs of life, it was clear no one would have survived.

We proceeded to the end of the road, where a golden monument stood high into the air. The stanchion holding it was clearly vandalized with etchings of remarks and names. Either the elderly gentleman who held the cord was not on watch 24/7 or the two kilometer distance had not deterred scoundrels from walking to this point.

As we had made our way from the checkpoint to the monument, the stark contrast between the two receding coast lines was ever more apparent.

The Indian Ocean raged on the south coast, where we had passed the remains of the cathedral. But only 100 meters away, the bay calmly pulsated. I imagined the cyclone washing over the small community some 50 years ago, leaving nothing in its wake but memories, and then violating the bay, distorting its history to this day.

Despite these cruel series of events, our varied group did manage to get a few pictures for posterity’s sake. We snapped photos together in order to commemorate our trip and new-found friendships. The driver even proudly commented he would place the Polaroid photo I gave him on his refrigerator. I sheepishly thanked him for safely guiding us to this point.

Our departure from Madurai five hours earlier included the three-hour journey to Rameswaram with the Rose Marie and Davenandran, who led the telemedicine project I had come to observe and the technician to assure its functional capacity, respectively.

Joseph had been alerted to my impending arrival by Rose Marie and joined our troupe at the telemedicine clinic. A man, no older than myself, he was easily the least-accented Indian I had met to this point, I asked if he had studied away from home when he mentioned he was in charge of the Rameswaram Trust.

Expecting that he must have studied in a native English-speaking country, or perhaps had lived there for quite some time before returning to his home town, he reported having only studied at a Seminary more inland than Rameswaram for a short time.

On our trip to the sea, he guided our troupe to a small fishing village where we stopped to check-in with a family he had known for quite some time. They were incredibly comfortable with me as a complete stranger and quickly offered food and drinks. I had not seen another Caucasian person in three days, so my presence was probably tempered by Joseph and Rose Marie. After some time catching up, none of which I could understand, we proceeded on.

On our path back, Joseph guided us to another home, where he introduced me to a woman who cared for the HIV+ fisherman whose numbers were creeping up in their community. She apparently did her best to also educate the townspeople of the treatment and safety of these men, all of whom had been outcast after their diagnosis was made. Joseph informed me this often fell on deaf ears.

By the time I returned to Madurai late that evening, I was exhausted but also fulfilled in the days events. It had been an unexpected event to be transported so far from the familiarity of Madurai, which I had known only for two days.

There had been little expectation on my part for what would occur on the way from Madurai to Rameswaram; even less so, the events of what transpired on our trip back to Madurai, most of which I have actually not documented here.

But the day fit with the nature of my overall journey so far, one which has been full of surprises, catching up with old friends, and making new ones. All the way from here to the sea.

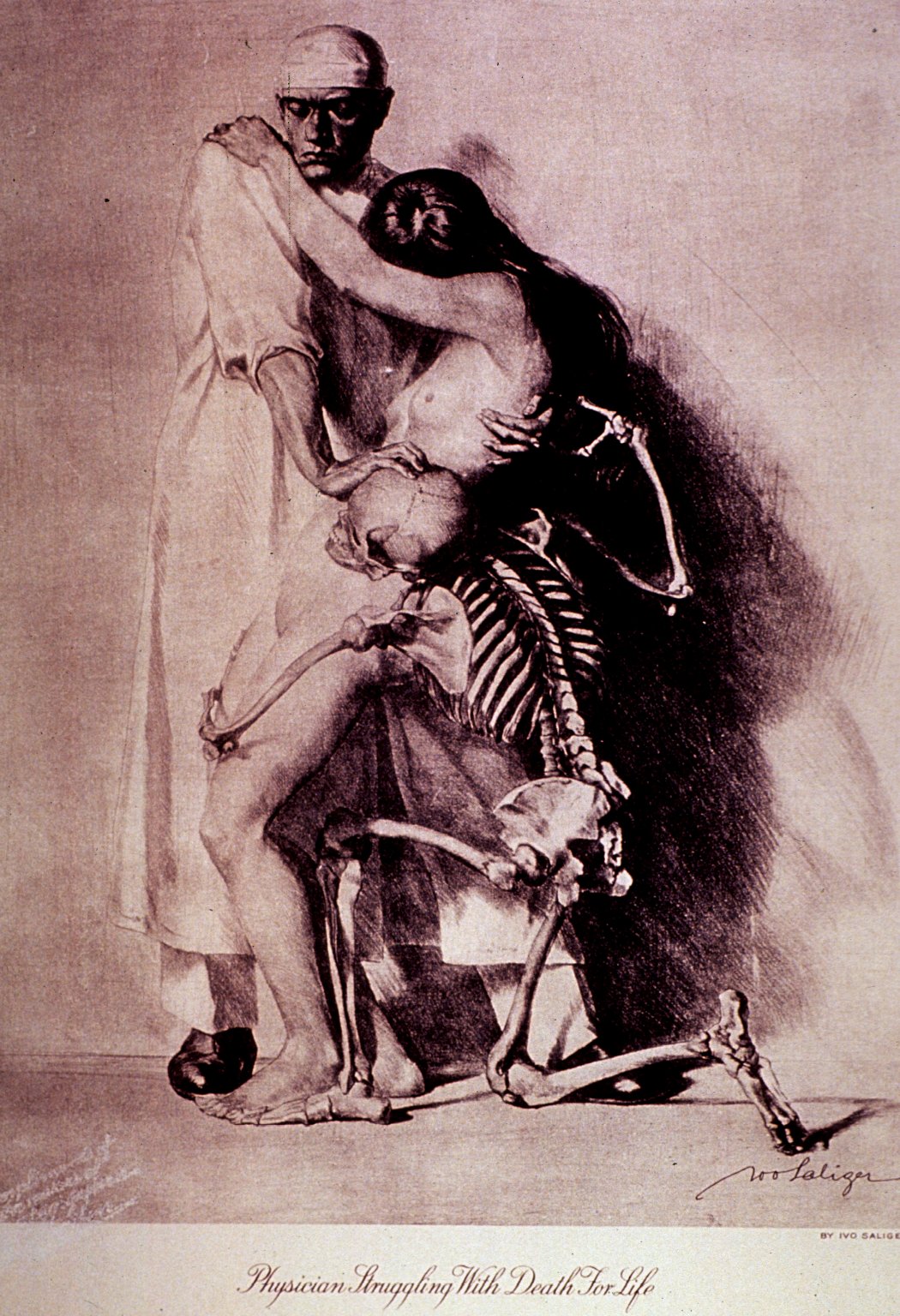

The Death of Magneto

Magneto was beginning to feel a cool wave of energy course through him. So close as to almost be one with him, Dr. Bett calmly placed his left hand on Magneto’s shoulder and his right hand, with stethoscope resting in the palm, against Magneto’s chest.

As calmly as the placement of his hand, came the words from Dr. Bett’s mouth.

“Don’t be afraid. Don’t run away- stay where you are.”

Magneto, born from tireless experiences of Intern year, knew a last gasp struggle with Dr. Bett would be moot. The poison Dr. Bett had so effortlessly and stealthily placed on Magneto’s mucous membranes was already causing a microscopic cascade of cellular apoptosis.

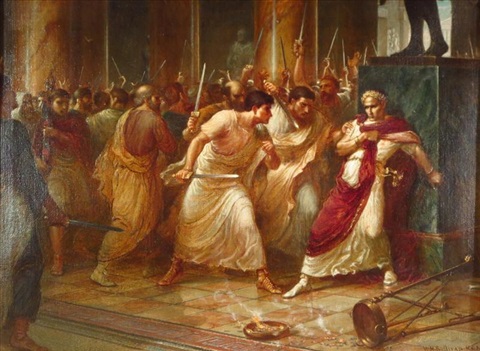

“Et tu, Dr. Bett?”

It was all Magneto could think to say in the moment before his death.

“Only Magneto had to die for this ambition,” responded Dr. Bett, recalling Brutus in the moments after he joined the assassination of Caesar.

Since his birth, Magneto had anticipated the greatest threat to his existence to come from his progenitor, Ean the Intern. From Ean’s grueling experience, Magneto had arisen as a counterbalance to the unbridled instincts and passion necessary for survival in Medical Residency.

Magneto had provided the organization and realization necessary to prevent Ean the Intern’s passions from destroying himself from within and ending this fantastic journey in its infancy.

Inadvertently, Magneto became the genesis for the Super Ego, Dr. Bett, who would become the moral compass on their tenuous journey.

Having given rise to Dr. Bett, Magneto was astounded of his own capabilities, but even more so, he was in awe by the strides Dr. Bett had made.

Each step Dr. Bett had taken brought Ean and Magneto closer to their ultimate goal. It also provided them even greater strength. His passion increasing along every one of Dr. Bett’s strides, Ean became harder for Magneto to control.

Magneto’s sole purpose now seemed to revolve around keeping Ean’s passions in check and preventing them from obliterating their common purpose as the completion of Residency loomed ever closer.

Dr. Bett had entrusted this responsibility upon Magneto, from which he expected a long and successful existence.

His last moments, so close to the end of their journey, had not been anticipated.

As the end of Residency became a reality, Dr. Bett began to feel the weight of Ean and Magneto with each step he took. While both had been necessary for his own creation, he could not envision the next journey coming to fruition if he would have to be responsible for them both.

This misunderstanding, which blinded Dr. Bett ever increasingly, gave rise to The Death of Magneto.

While Ean could at times create trouble if not adequately balanced by Magneto, Dr. Bett believed Ean’s instincts to be invaluable to their next journey. Simultaneously, Magneto’s own strength, as a counterbalance and as his own entity, could not be overlooked.

Dr. Bett, after painful deliberation, could see Magneto becoming too powerful to control due to the opportunities awaiting them on their next journey. Eventually, Magneto’s strengths could make Dr. Bett unnecessary.

More importantly, Magneto’s relationship with Ean, while needed at this stage, was not deemed to be necessary by Dr. Bett in the future. Dr. Bett could harness Ean’s energy on his own.

And if Magneto eventually realized that Ean was beholden to him, and not Dr. Bett, it would be Magneto, and not Dr. Bett, who would truly be in charge of this journey.

This was a reality Dr. Bett was not willing to allow.

There was a brief moment when Magneto looked into Dr. Bett’s eyes as his vision blurred and the sound of his own heart faded.

Dr. Bett looked as caring and thoughtful as ever.

It was a moment not foreseen by Magneto. But he was comforted by it.

That was the moment. The Death of Magneto.

A Week in April

I had four patients die within one week.

When the totality hit me, I nearly lost control of my emotions.

On the Obstetrics service, a majority of all patient encounters are joyous and professionally reaffirming.

Each antepartum heart tone heard via ultrasound brings a sense of wellness and anticipation, both to the expectant mother and the caring physician.

But not every delivery has a pleasant outcome. Not every parent has a sense of anticipation. And not every physician can cope with those competing forces.

I delivered a 33-week-old neonate who precipitously declined within the first 24 hours of life. It had been an easy delivery, with the mother having given birth five times previously, and the fetus not yet having reached the period of greatest growth.

With one deep breath from her mother and a hearty push of the abdominal and pelvic musculature, the baby arrived, opening her eyes and taking her first breath while still cradled in my left arm.

She looked right at me. Deep into my eyes as she let out her first cry.

But despite our medical technologies and painstaking care, not every newborn baby survives.

She died in the neonatal intensive care unit 7 days later, an infection having made its way from the vaginal mucosa of her mother into her lungs and from there into her bloodstream.

The most aggressive antibiotics and procedures did not save her; there was nothing more we could have done.

Her death was unsettling. It came as the last of the four, but the one which nearly encompassed my entire being in darkness.

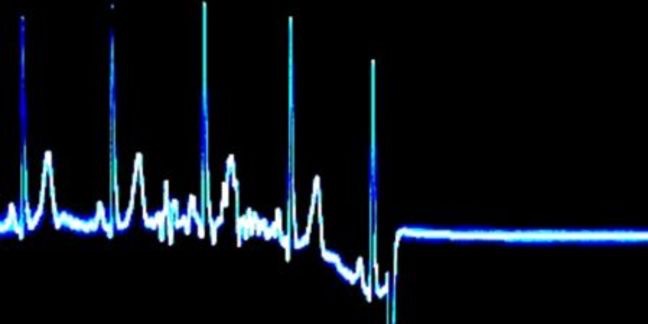

Two days after her birth, while awaiting another delivery on a quiet Friday night, the Code Blue alarms, indicating a cardiac arrest somewhere in the hospital, sounded overhead in the lecture hall.

My colleague, Dr O, was on medicine call that evening; she jumped from her seat across from me, immediately ending our conversation.

I glanced at my other colleagues remaining at the table and dutifully indicated I would join Dr O in case she needed back-up so they could complete sign-out.

The Code was called to a room at the furthest point possible from where we were seated, so rather than assuming I would eventually arrive to find Dr O having resuscitated the patient, I broke into a full sprint, clasping my stethoscope around my neck with my right hand to prevent it from flying off mid-stride, in case something went awry.

When I arrived a minute later, all hell was breaking loose, despite Dr O and a more senior physician, Dr B, deftly providing and directing life resuscitating efforts.

The woman, a 31-year-old mother of 6, who was admitted for nausea two days earlier, was accompanied in the room by her distressed and screaming 6-year-old son and her husband, who was shouting hysterically from her bedside, begging her to come back.

I stepped into hell incarnate and helped guide the husband and son to an adjoining room.

When I returned moments later, nothing had changed. She was still unresponsive. No heart beat was palpable; no rhythm identified on the cardiac monitor.

A deep sense of distress was evident in the room, despite the aggressive nature of our efforts.

The next hour lasted for an eternity, as Dr O, Dr B, and myself assisted the nurses in providing chest compressions, giving medications to stimulate cardiac contractility, and delivering electrical shocks to bring her back to life.

Nothing worked.

Her heart did not regain electrical activity. Her lungs did not attempt another breath.

Once we determined further efforts were futile, the husband, increasingly hysterical, was guided back into her room, to kiss the cheek of a lifeless body once belonging to the mother of his 6 children.

He begged us to try more. The despair in his eyes pierced everyone’s souls.

His son was sitting quietly in the adjoining room.

Physicians, nurses, security guards, and the chaplain cried; our emotions audible throughout the hallway.

I returned to the Obstetric floor after embracing my colleagues in a moment of silence. I stopped in the locker room to take off my sweat and tear-soaked scrubs and replace them with a new pair.

I delivered a healthy baby boy an hour later. His parents thanked me incessantly before I left the room.

I left the hospital the following Saturday morning having delivered several newborn girls and boys into this world.

All the while knowing a loving mother had unexpectedly died and another child’s life was being sustained in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit.

When I returned to the hospital on Sunday night, I quickly scoured the electronic charts awaiting my signature.

A new electronic tab had appeared in the toolbar for me to click on. It read “Death Notice.”

I anticipated having to re-read the harrowing and emotional report of the unexpected death of the mother from Friday night.

Instead, I was blindsided by the account of another of my patient’s death, whom I had seen only a few weeks previously in the office.

He had been brought to my hospital’s Emergency Department on Saturday night, lifeless, despite the heroic efforts of the EMS and subsequent attempts by the Trauma Surgeons.

In the early evening hours of Saturday night, he had been found lying in a pool of his own blood, a trail of that blood following him for a reported 50 yards.

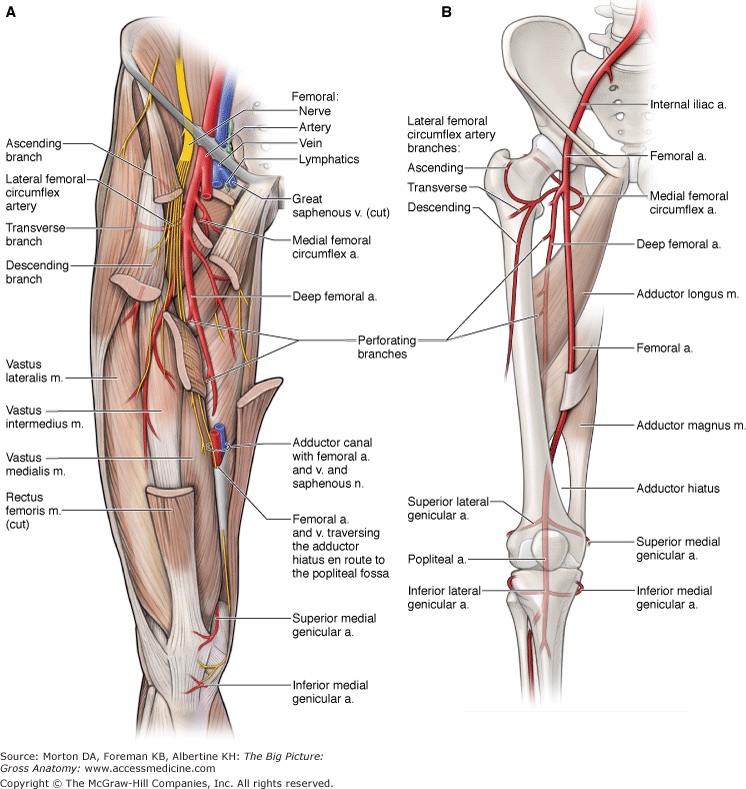

A bullet had pierced his femoral artery, the largest blood-carrying vessel in the leg; it had shredded the artery, leaving behind a capable exit path for the blood to flow from his body.

With each beat of his heart, more blood would gush from the wound in his leg, causing the heart to beat faster as it attempted to compensate for the missing blood.

Instead of a life-continuing effort, in its paradoxical nature, the heart beckoned the same death it hoped to avoid.

After scouring the internet for more information, I learned the 50-year-old man had been minding his own business in the parking lot of his apartment building when a man and woman approached him. They pointed a gun at him and demanded his wallet.

Having had several colorful conversations with him in the office, I could easily visualize him telling them to “Fuck Off”, his East Coast upbringing shining bright.

The following morning I received a phone call from my Program Director. She had also received notification of his death and wanted to check in with me.

I expressed my thanks for her concern. I did not tell her about the lifeless mother or the neonate only a few breaths from death.

A third patient died in the next 48 hours.

Honestly, I can not recall the details. None of them.

They have seemingly been erased from my memory, perhaps in a fitful effort to suppress the emotions death has brought to the forefront of my medical training so that I do not throw my heart up in the air and declare all is lost.

But I know another patient, someone for whom I cared, whose family loved them, succumbed to the only outcome known to our species.

Death.

So I will document that death here; despite my brain’s greatest efforts to forget it, I will forever know the impact it has had upon me.

When I received the call, I let out a deep sigh. I hung up as my eyes swelled with tears.

The fourth death. A seven-day-old child whose eyes I had stared into while holding in my left arm as she took her first breath.

Until the day I die, I hope to not forget the look I gave her. One of awe. And love. Excitement. And fear.

A gamut of human emotions, packed into one soul-penetrating experience.

I hope, despite her struggle for life, that in her final moments, the neurons in her brain grasped onto the emotions I transferred to her with our brief encounter.

That in the last beat of her heart and breath of her lungs, her mind went to the moment we shared; the look of awe and love and excitement drowning out the fear lurking deep in my eyes.