A Week in April

I had four patients die within one week.

When the totality hit me, I nearly lost control of my emotions.

On the Obstetrics service, a majority of all patient encounters are joyous and professionally reaffirming.

Each antepartum heart tone heard via ultrasound brings a sense of wellness and anticipation, both to the expectant mother and the caring physician.

But not every delivery has a pleasant outcome. Not every parent has a sense of anticipation. And not every physician can cope with those competing forces.

I delivered a 33-week-old neonate who precipitously declined within the first 24 hours of life. It had been an easy delivery, with the mother having given birth five times previously, and the fetus not yet having reached the period of greatest growth.

With one deep breath from her mother and a hearty push of the abdominal and pelvic musculature, the baby arrived, opening her eyes and taking her first breath while still cradled in my left arm.

She looked right at me. Deep into my eyes as she let out her first cry.

But despite our medical technologies and painstaking care, not every newborn baby survives.

She died in the neonatal intensive care unit 7 days later, an infection having made its way from the vaginal mucosa of her mother into her lungs and from there into her bloodstream.

The most aggressive antibiotics and procedures did not save her; there was nothing more we could have done.

Her death was unsettling. It came as the last of the four, but the one which nearly encompassed my entire being in darkness.

Two days after her birth, while awaiting another delivery on a quiet Friday night, the Code Blue alarms, indicating a cardiac arrest somewhere in the hospital, sounded overhead in the lecture hall.

My colleague, Dr O, was on medicine call that evening; she jumped from her seat across from me, immediately ending our conversation.

I glanced at my other colleagues remaining at the table and dutifully indicated I would join Dr O in case she needed back-up so they could complete sign-out.

The Code was called to a room at the furthest point possible from where we were seated, so rather than assuming I would eventually arrive to find Dr O having resuscitated the patient, I broke into a full sprint, clasping my stethoscope around my neck with my right hand to prevent it from flying off mid-stride, in case something went awry.

When I arrived a minute later, all hell was breaking loose, despite Dr O and a more senior physician, Dr B, deftly providing and directing life resuscitating efforts.

The woman, a 31-year-old mother of 6, who was admitted for nausea two days earlier, was accompanied in the room by her distressed and screaming 6-year-old son and her husband, who was shouting hysterically from her bedside, begging her to come back.

I stepped into hell incarnate and helped guide the husband and son to an adjoining room.

When I returned moments later, nothing had changed. She was still unresponsive. No heart beat was palpable; no rhythm identified on the cardiac monitor.

A deep sense of distress was evident in the room, despite the aggressive nature of our efforts.

The next hour lasted for an eternity, as Dr O, Dr B, and myself assisted the nurses in providing chest compressions, giving medications to stimulate cardiac contractility, and delivering electrical shocks to bring her back to life.

Nothing worked.

Her heart did not regain electrical activity. Her lungs did not attempt another breath.

Once we determined further efforts were futile, the husband, increasingly hysterical, was guided back into her room, to kiss the cheek of a lifeless body once belonging to the mother of his 6 children.

He begged us to try more. The despair in his eyes pierced everyone’s souls.

His son was sitting quietly in the adjoining room.

Physicians, nurses, security guards, and the chaplain cried; our emotions audible throughout the hallway.

I returned to the Obstetric floor after embracing my colleagues in a moment of silence. I stopped in the locker room to take off my sweat and tear-soaked scrubs and replace them with a new pair.

I delivered a healthy baby boy an hour later. His parents thanked me incessantly before I left the room.

I left the hospital the following Saturday morning having delivered several newborn girls and boys into this world.

All the while knowing a loving mother had unexpectedly died and another child’s life was being sustained in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit.

When I returned to the hospital on Sunday night, I quickly scoured the electronic charts awaiting my signature.

A new electronic tab had appeared in the toolbar for me to click on. It read “Death Notice.”

I anticipated having to re-read the harrowing and emotional report of the unexpected death of the mother from Friday night.

Instead, I was blindsided by the account of another of my patient’s death, whom I had seen only a few weeks previously in the office.

He had been brought to my hospital’s Emergency Department on Saturday night, lifeless, despite the heroic efforts of the EMS and subsequent attempts by the Trauma Surgeons.

In the early evening hours of Saturday night, he had been found lying in a pool of his own blood, a trail of that blood following him for a reported 50 yards.

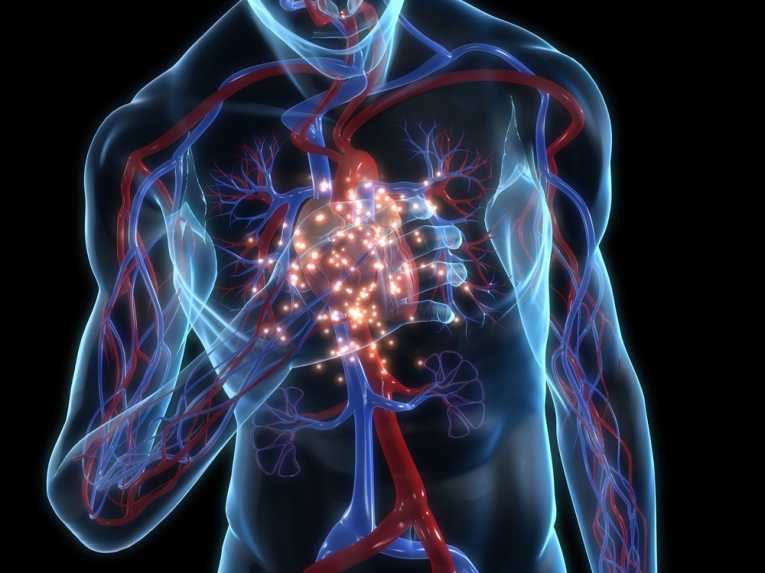

A bullet had pierced his femoral artery, the largest blood-carrying vessel in the leg; it had shredded the artery, leaving behind a capable exit path for the blood to flow from his body.

With each beat of his heart, more blood would gush from the wound in his leg, causing the heart to beat faster as it attempted to compensate for the missing blood.

Instead of a life-continuing effort, in its paradoxical nature, the heart beckoned the same death it hoped to avoid.

After scouring the internet for more information, I learned the 50-year-old man had been minding his own business in the parking lot of his apartment building when a man and woman approached him. They pointed a gun at him and demanded his wallet.

Having had several colorful conversations with him in the office, I could easily visualize him telling them to “Fuck Off”, his East Coast upbringing shining bright.

The following morning I received a phone call from my Program Director. She had also received notification of his death and wanted to check in with me.

I expressed my thanks for her concern. I did not tell her about the lifeless mother or the neonate only a few breaths from death.

A third patient died in the next 48 hours.

Honestly, I can not recall the details. None of them.

They have seemingly been erased from my memory, perhaps in a fitful effort to suppress the emotions death has brought to the forefront of my medical training so that I do not throw my heart up in the air and declare all is lost.

But I know another patient, someone for whom I cared, whose family loved them, succumbed to the only outcome known to our species.

Death.

So I will document that death here; despite my brain’s greatest efforts to forget it, I will forever know the impact it has had upon me.

When I received the call, I let out a deep sigh. I hung up as my eyes swelled with tears.

The fourth death. A seven-day-old child whose eyes I had stared into while holding in my left arm as she took her first breath.

Until the day I die, I hope to not forget the look I gave her. One of awe. And love. Excitement. And fear.

A gamut of human emotions, packed into one soul-penetrating experience.

I hope, despite her struggle for life, that in her final moments, the neurons in her brain grasped onto the emotions I transferred to her with our brief encounter.

That in the last beat of her heart and breath of her lungs, her mind went to the moment we shared; the look of awe and love and excitement drowning out the fear lurking deep in my eyes.