The Opposition to Magneto

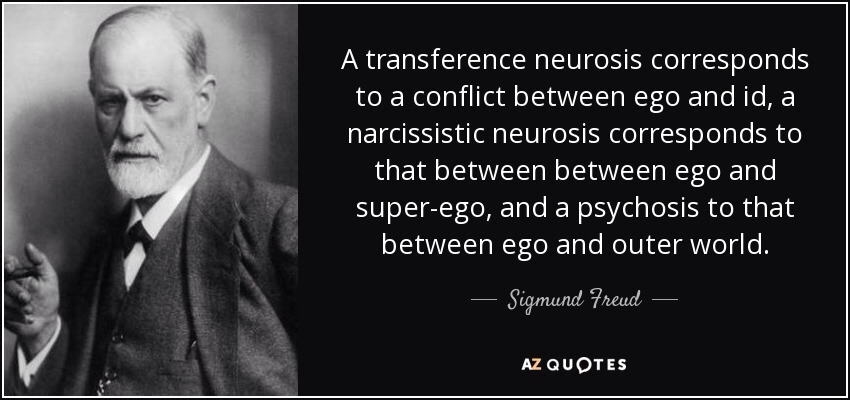

Almost 100 years ago, the world-renowned psychologist Sigmund Freud unleashed his theory of the human psyche. He theorized our being to be composed of three parts, each of which develops at different but early stages of our life; eventually, each is meant to interact simultaneously to help us navigate our world.

If Freud’s theory is accurate, my Id, Ego, and Superego completed their development nearly 30 years prior to my first day as a Resident Physician. But in the course of reflecting on the end of my second year of Residency, I have discovered a new wrinkle to Freud’s century-old theory.

In The Rise of Magneto, I thought about:

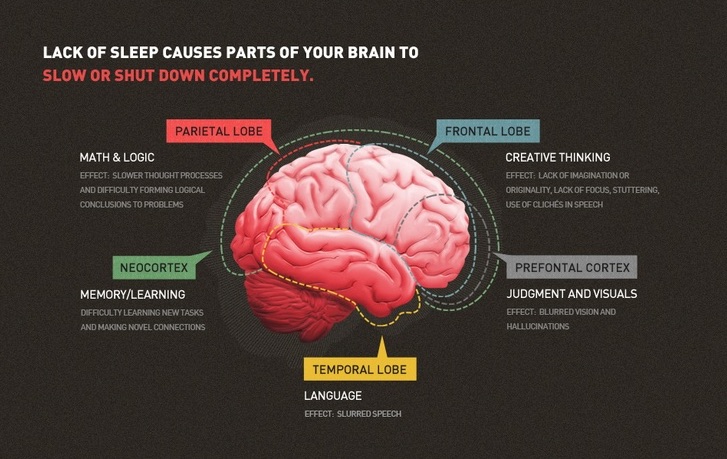

The transition from “medically knowledgeable but clinically deficient intern” to “clinically seasoned and seemingly knowledgeable Senior Resident” is fraught with pitfalls: sleep deprivation, anxiety-producing clinical scenarios, life-and-death struggles, and glaring holes in medical knowledge.

Nearly six months have passed since I described the The Rise of Magneto, the alter-ego bestowed upon me in the heat of a tussle with Black Betty (Night Float), and I have found the term “alter-ego” to be a slight misnomer; Magneto is my new Ego, not simply an alternate.

Freud described the Ego as ‘that part of the id which has been modified by the direct influence of the external world.’ In my case, Magneto is the result of my Id having experienced the responsibility, stress, failures, and successes of becoming a physician.

If Magneto is my Ego, then the other components of my psyche, the Id and Superego, are somewhere, developed and competing amongst the other experiences of Residency. If Freud’s theory is accurate, they are, in effect, The Opposition to Magneto.

My Id was the primitive and instinctive component of who I was before Residency: Ean, a 34-year-old grown man who had completed medical school as part of a greater mission.

In his initial introduction to the responsibility of being a physician, Ean the Intern could engage in what Freud described as primary process thinking; an amalgamation of my primitive, illogical, irrational, and fantasy-oriented beliefs emboldened in medical school. (Ex. Engaging in a tit-for-tat with my senior Resident on my first go-round of Black Betty.)

As Ean the Intern’s experiences in Residency began to mold him, Magneto developed to mediate the unrealistic Id and the external world. No longer was I left to the primary process thinking of Ean the Intern, relegated to the impulsive and unconscious desires of a newly-minted physician.

Instead, Magneto brought secondary process thinking, which is rational, realistic, and oriented towards problem-solving. (Ex. Strapping a magnet to the chest of a dying woman to deactivate her pacemaker so I could carry on with the multitude of other patients awaiting my care).

Now, as I become a PGY-3, my Superego, the last bastion of development per Freud, is taking shape in the form of Dr. Bett the Attending. My psyche’s most mature aspect, the Superego serves two purposes:

1) control the impulses of the Id (Ean, the primitive and fantasy-oriented Intern)

2) persuading my Ego (Magneto, the Senior Resident) to turn to moralistic goals and to strive for perfection

According to Freud, Dr. Bett the Attending incorporates the learned values and morals of medical society into the completed psyche, previously only constructed by Ean the Intern and Magneto, in order to create a fully-functional physician.

During this second year of Residency, Magneto has struggled to fulfill his obligations to the psyche; it is a constant uphill battle, trying to work out realistic ways of satisfying Ean the Intern’s demands, while simultaneously trying to live up to the expectations of Dr. Bett the Attending.

Freud made the analogy of the Id being a horse while the Ego is the rider. The Ego is ‘like a man on horseback, who has to hold in check the superior strength of the horse.’

In my case, Magneto, the Senior Resident, has to hold in check the primitive and unbridled passion, rage, joy, and false-beliefs of Ean the Intern. While harnessing the emotional energy of Ean the Intern, Magneto must institute a plan of action to carry forth the solution to whatever problem arises.

In the horse and rider analogy, Freud believed the Ego to be weak relative to the headstrong Id, simply doing its best to stay on; in effect, Magneto simply pointing Ean the Intern in the right direction, trying to claim some credit for the successes therein.

Meanwhile, in Freud’s psyche construct, the Superego, Dr. Bett the Attending, watches Magneto try to control Ean the Intern from afar, via his two components: The conscience and the ideal self.

Dr. Bett’s conscience can punish Magneto when he gives in to Ean the Intern’s demands by creating feelings of guilt.

Simultaneously, Dr. Bett’s ideal self exists as an imagined construct of who he should be, representing career aspirations and how to behave as an established member of the medical society.

Magneto is nearly constantly trying to live up to the expectations of Dr. Bett while attempting to prevent Ean the Intern from derailing Dr. Bett’s ideal self. And when successful, Dr. Bett rewards Magneto with feelings of pride.

In nearly every action, Magneto, the Senior Resident, reflects back on the do-or-die nights, the life-and-death days, the thankful patients, the grateful families, the new-born babies first squeal, and the meaningful and life-long relationships created in the cauldron of uncertainty that brought on his own existence…

The Id. The Ego. The Superego.

Each acting in concert, for perpetuity; the Id and Superego, tugging at Magneto, drawing on his energy, forever acting as the Opposition to Magneto.