Exercising the Demons

Scott and I walked into his apartment a bit lighter in the pockets and mildly sleep-deprived. The drive back to Los Angeles hadn’t been more than 4 hours, mostly through the barren desert highway, but it had given us plenty of time to reminisce on the previous 24 hours.

His roommate greeted our return with, “Hey, where did you guys stay in Las Vegas?”

Scott replied, “Oh, just some low-class Motel 6 off the strip.”

She pointed quizzically at the newscast on the TV screen. “You mean that Motel 6?”

We replied simultaneously, “Yeah, why? What’s going on?”

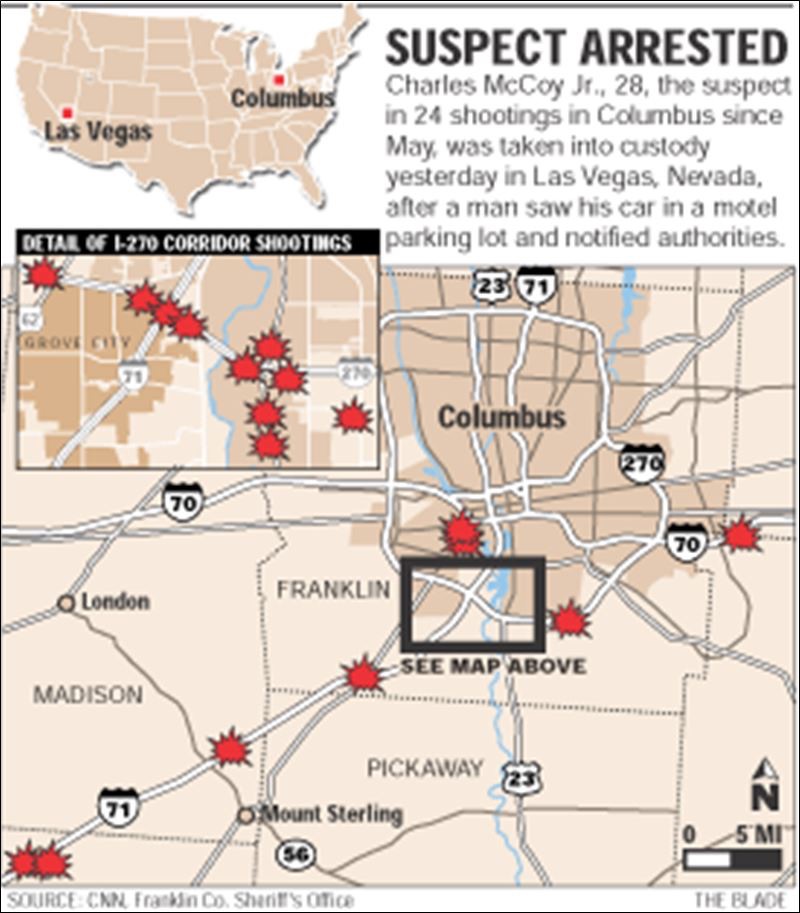

“A few hours ago they caught the sniper there who had been killing people in Ohio.”

I looked at Scott. He looked at me with the same look of disbelief.

We had unknowingly had an uncomfortably close brush with infamy.

The “270 Sniper” had been caught at our hotel in Las Vegas a mere 60 minutes after we departed.

We had spent the previous 24 hours gambling, drinking, and wandering the streets of Sin City. He had been hiding in our Motel 6, law enforcement hot on his trail.

So when Scott and I recently planned a return trip to Las Vegas twelve years later, we decided to class it up a bit, avoid the Riff Raff, and stay on the strip.

There was no telling whom we would encounter this time around, but we actively sought to avoid any serial killers at The Motel 6.

Scott and I have known each other since 8th grade. His and my parents shared the odd predilection for sending their children to a brand new school housed in a warehouse in the industrial sector of Wichita, KS.

Yes, we went to school in a warehouse. Not like something out of a Philip K. Dick novel, where we would by psychologically programmed to become superhuman automatons.

But more like a once-vibrant warehouse in the process of being transformed into a new age educational experience where grades were in flux and Love was bountiful.

Actually, Love was very bountiful there, as the up-start school was housed in a Love Box Company warehouse, likely something Walter Love, the company’s founder, would have beamed with pride about.

While there, Scott and I both were indoctrinated in Logic, Composition, Biology, and Roller Hockey {in reverse order of importance}.

Despite the humble beginnings of our friendship, in a warehouse school in a dusty midwest metropolis, the lessons we learned were paramount to our unlikely professional ascensions. [Except for the Roller Hockey. I don’t really use that for anything.]

Our friendship started over twenty years ago in a warehouse.

Then we managed to avoid a psychopathic serial killer 10 years later.

Now, only a few weeks ago, we found ourselves re-united in Sin City again.

In the midst of Residency, it has been hard for me to “catch my breath” at times. The completion of every shift, every day in the office, and every licensure task, brings on more things to do, more days in the office, more shifts to be worked.

It seems inescapable.

But that’s why it’s called Residency. In order to be trained properly and efficiently, you are seemingly living at the Hospital, in the office, or a desk trying to complete a seemingly endless list of tasks.

Which is why Scott’s suggestion of a reunion in Las Vegas was utterly brilliant. We both needed a breather from our action packed lives.

Over ten years after our brush with infamy, Scott and I are living lives we simply couldn’t have imagined back then. Scott is a successful Healthcare Systems analyst, having completed his PhD at Florida State after marrying a hometown girl, and now resides in our nation’s capitol with a daughter and another one on the way.

We have kept in close touch since our last destination vacation to Sin City, but if the last 10 years taught us anything, it was to upgrade from The Motel 6.

When I made my egress from the plane in Las Vegas on Sunday morning, Scott was there waiting; the mastermind to our 48 hour get-away already had the wheels in motion.

We made our way to the Uber pick-up and our driver quickly made a quick connection, identifying that his grown children live in the same city as me. The small talk was brief, as it only took 5 minutes to reach our destination.

Our destination, the MGM Grand, was a familiar location to Scott, as he had visited Sin City numerous times in the years since our last sojourn together; most typically he arrived with his wife, who would be the Chris Moneymaker to his Phil Hellmuth in a pairing of Poker legends.

But this time, he managed to wrangle a male side-kick, in a Zach Galifianakis in “The Hangover” mold, rather than a Johnny Chan.

At the MGM, Scott managed to finagle an earlier-than-typically-allowed check-in time by not-so-secretively leaving a $50 tip for the concierge. As we calmly and cooly proceeded towards our rooms, I had the feeling our 48 hours of escape in Las Vegas would easily eclipse the 24 hours of chaos we spent there over a decade earlier.

When I landed back in Columbus on Tuesday evening it was nearly midnight. I was exhausted; and sun-burned. And slightly enamored with a woman I met on a plane.

In addition, I was neither psychologically or physiologically prepared to be a physician again in less than 8 hours.

But in Vegas, when the stakes are high, you can either fold or go all-in. I decided to go all-in this time.

We may not have had an indirect brush with infamy like back in 2004, but our 48 hours in Sin City made us hungry for more; just as with the genesis of our friendship, there would likely be more tales to tell.