Black Betty

At 2:17AM on a recent Friday morning I couldn’t sleep.

Not in the sense that I was laying awake in bed, thinking about the cosmos, or wondering how “The Walking Dead” Season Finale would play into any future cross-over series that might be developed, or anxiously awaiting the sun to rise again.

I was actually physically not able to sleep.

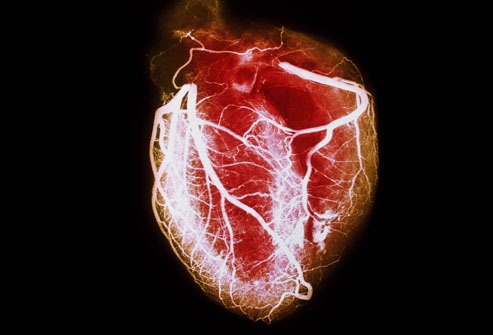

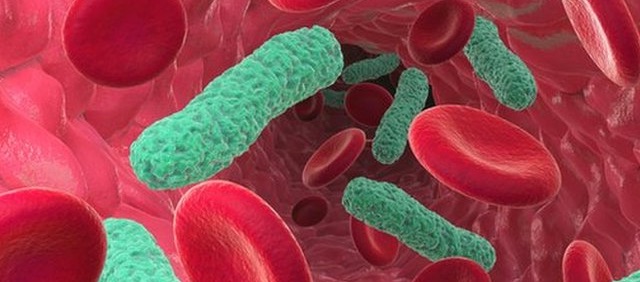

As my body was beginning to shut down at the cellular level, the efflux of potassium and phosphorus from every cell beginning to overwhelm my blood stream, the pager holstered upon my left hip started chiming again.

The pager transmitted electrical energy, similar to that of a defibrillator, into my body; the potassium and phosphorus blasted back into the cells, preventing a super-saturated metabolic derangement which would have caused my cardiac activity to cease.

Simultaneously, the loudspeaker in the Emergency Department blared, “Septic Shock Alert, ED 47.”

“Septic Shock Alert, ED 47.”

I unholstered the pager from my hip, quicker than Doc Holliday when he penetrated Ringo’s brain with a lead slug, and glanced down at the message awaiting me.

As I swiveled and rose from the stool I had been atop for only a matter of moments, I read the message. Thankfully, it only read “Septic Shock Alert, ED 47”, the electrical companion to the overheard communication, instead of 555-9095.

Or 555-9030.

Or 555-9494.

Those numbers belonged to the Hospitalist medicine service, the Intensive Care Unit, and the ED Nursing desk, respectively.

Responding to any of those calls would have meant either another patient was waiting for me to admit them to the hospital or an already admitted patient was trying to die in the ICU.

If any of those three numbers had been present, I would have needed to take over the care of the actively dying patient in the Septic Shock Alert, while simultaneously trying to:

1) figure out how in god’s name I would possibly get all of the work done I still had to do

2) supervise my junior resident

3) not lose my mind.

I also probably would have taken the pager and rifled it into the closest wall, hoping to have it explode in a wave of energy like the Death Star in Episode IV.

My Junior Resident sat beside me, near catatonic from Night Call’s siren song; I tugged at his scrub top, motioned for him to follow along, and let out a long sigh.

I could not sleep.

I was the Senior Resident on Night Call.

Or as I prefer to call her, Black Betty.

Black Betty is the anthropomorphic representation of Night Call, the overnight shift when physician staffing drops to a skeleton crew and the statistical probability of all hell breaking loose starts creeping up on 100%.

As the sun begins setting on a hard day’s work for most of the physicians, nurses, and ancillary staff in the hospital, Betty begins to rear her ugly head.

Her darkness requires the fortitude of a special type of physician.

Unless you are a Resident like me. Then you are required to show up to spend some time with Black Betty as a part of your training.

You are not a special physician. You are a Resident. And the only thing special about you is your ability to not spontaneously combust from the lack of sleep you have sustained.

Every Resident dates Black Betty. Some for a night here and there, with no specific frequency or expectation. She does not discriminate.

Others join her for a two week stretch; where her smooth skin becomes chapped and dry by the third night, her velvety caressing hands become stiff and arthritic by the seventh, and her formerly gentle kisses become vicious flesh-tearing wounds as the sun rises on the tenth.

Black Betty invites the denizens of the night to start shuffling into the Emergency Department.

And the critically ill whose lives are sustained by technological marvels in the ICU to begin their physiologic derangements.

They are joined by the sickly and elderly who become unpleasantly delirious as a result of her rancor.

—–

To this point in my Residency, I have spent over 20 weeks with Black Betty. A majority of those weeks have come in two week chunks, spread over In-patient Medicine, Surgery, and Obstetrics.

But as a now as a PGY-2, the Senior Resident, I have also had more than my fair share of random Saturday date nights with ‘ol Betty.

She and I have been intimate more times than I would care to admit.

Each date brings about something unique, whether it’s a patient hurtling a chair through a 7th-story window, a near-dead woman’s heart beating in full view of the audience in the trauma bay, or stabbing a needle into a man’s chest to hear the whoosh of air escape and provide his lung the opportunity to re-inflate.

She is fertile with opportunities for us to perform our duties as physicians.

Black Betty had a child, the damn thing gone wild.

At 2:43AM on a recent Friday morning I exited ED 47 with my Junior Resident in tow.

Black Betty had provided us an opportunity to exercise our clinical judgement, initiate resuscitative measures, and stabilize an elderly gentleman who had tangoed with the Grim Reaper several times in the past two months.

The Reaper’s grasp had tried to choke off the man’s air supply. But we would have none of that.

Black Betty didn’t care. She shrugged it off.

She knew other opportunities awaited.

And my Junior Resident and I would be there. Waiting.

I would not sleep.

Not when Black Betty has anything to say about it.