the one percent

—–

In the Fall of 2011, while in the midst of studying for my first medical licensing exam, a time period in which most students become so immersed in learning the filtration properties of the proximal convoluted tubule of the kidney that they can’t tell you the day of the week, I managed to catch a glance of the New York Times every once in a while.

What I saw was amazing; the type of social uprising with which Stalin would have thought intriguing. My interest in Occupy Wall Street, bristling in nYc’s Zuccotti Park, stemmed more from an educated curiosity than a support of the movement, but its occurrence and my observance provided a daily reprieve from the mind-numbing studying.

—–

—–

And perhaps more importantly, if everything went as planned, if all of my hard work, hours of memorization, and time spent differentiating between the etiologies of monocular glaucoma and retinal detachment, I would become part of a different one percent.

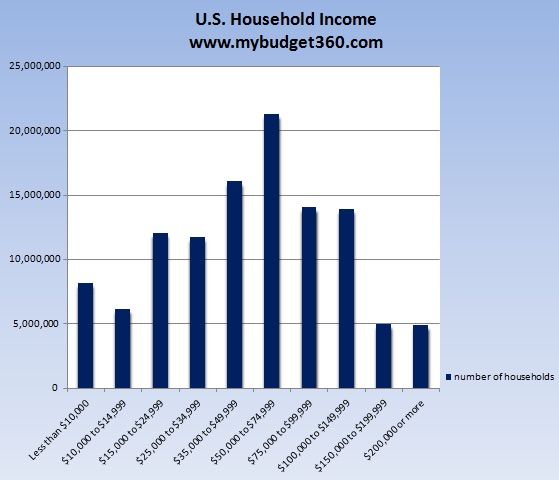

The Occupy Movement, as it became known, was an example of the age-old battle between the “haves” and “have nots”, except on a grander scale, as the “have nots” were meant to be representative of the 99% of American’s who do not possess the majority of our Nation’s private wealth. Wall Street, with it’s perceived “fat cat” mentality, was the optimal target, emblematic of the wide gulf between wealth and poverty in our country.

—–

—–

My curiosity was piqued for multiple reasons, not only because of the precipice on which I found myself, but because I believed our immediately digital world was bringing this tale directly into anyone’s home who was willing to log on to the internet, click a link on YouTube, or haphazardly skim a front page article in any leading newspaper.

It’s not as if I was surprised by the willingness of many Americans to embrace the Occupy Movement (until it descended into mass chaos); most Americans long for the financial independence they feel has been squelched by the One Percent.

—–

—–

Given my education and opportunities I have been and will be afforded because of it, I have a hard time agreeing with that mentality. The economy does not work in a way that is “understandable” to most Americans; I don’t mean to belittle the knowledge of most Americans, but I truly believe it.

The economy on which America was founded basically depends on such a massive inequality between the 99% and their villainous opposition.

Yet, I digress, as the One Percent I associate myself is not the behemoths of industry, finance, and politics embodied in the fervor of the Occupy Movement. Instead, my access point to the One Percent is my profession: a physician in America.

—–

—–

When I awoke from the immersed slumber of studying for the aforementioned medical licensing exam, which once passed allows medical students to participate in patient care in a hospital setting, I had ample time to re-acclimate myself to the goings-on of America. At the forefront was the Occupy Movement, which in Boston where I resided, was taking place not far from South Station.

While awaiting my 3rd year of medical school schedule, I decided to journey to several major cities on the East Coast and Midwest where I might be placed in order to investigate the hospitals at which I might train; or choose not to train at, depending on what I concluded.

Included in this whirlwind was New York City, the birthplace of the Occupy Movement.

—–

—–

My association with the One Percent is not one I am “excited by”, as in, I am not looking forward to the day when I am afforded financial independence because I am a well-compensated physician. In fact, at no time in the entire process of deciding to reverse course on my entire professional career and become a physician was I motivated by the idea of making money.

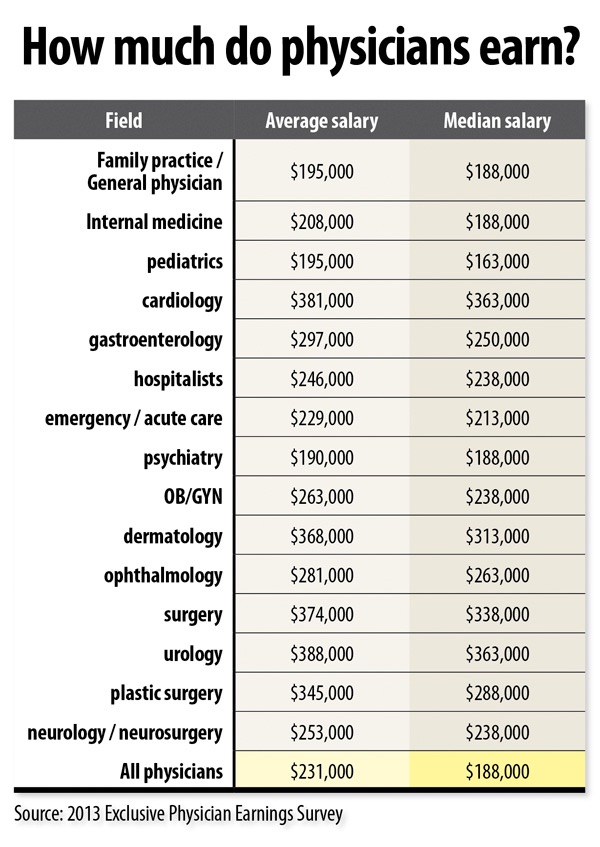

This is due in most part to the reality of having a much more lucrative career in any number of other fields without incurring such massive financial debt in the process. Despite such a fact, the average income of a physician, even when including paying off said debt, will afford a comfortable salary and lifestyle (idiotic purchasing habits and tendency to live outside of exorbitant means, notwithstanding).

—–

—–

And so it is this fact, the one in which I possess an education which allows me to be well-compensated, that puts me in an overlying bracket of the One Percent.

I certainly do not anticipate accruing the assets necessary to be part of the 1% of Americans who possess >50% of the individual wealth in this country, the scourge of the Occupy Movement, but I do possess an education far more in-line with the ability to do so than a massive majority of people.

Yet, within my colleagues, I have experienced a disconnect with these facts. Even in my current physician standing as a Resident, in which my salary is fixed despite the hours I practice, my income is larger than the average American family of four.

—–

—–

I repeat, my income as a single, white, male is larger than the typical American family income.

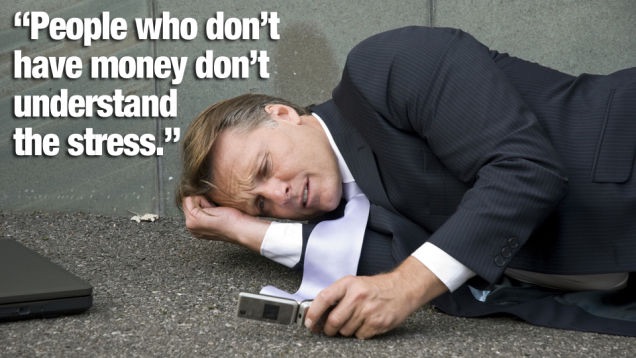

An example of this disconnect arose when my fellow Residents and I were gathered together to sign new contracts for the up-coming year. Our Program Director made a quick joke about our slight increase in pay, which was lamented by one of my colleagues.

She noted how awkward it was that hourly employees of the hospital could be rewarded with an end of the year bonus, but our current status as Residents, prevented us from any such potentiality.

Our program director quickly pointed out how despite our “low-wage” we still made significantly more than an hourly employee who was eligible for an end-of-the-year bonus.

—–

—–

Such a disconnect is not uncommon within the Resident physician echelon, as I have been hearing about it from every friend and colleague in the medical field since long before I joined their ranks.

But for my salary, in two years it will double. Or triple. Or quadruple. Or quintuple… or… whatever I want it to do depending on the number of hours I want to work, the type of physician practice I join or don’t join, the geographic area in which I live, and any number of other factors I chose to include.

To have those options almost seems ludicrous to me. But they are true.

And at times, the possibility of making a salary more recompense with my education and expertise enters my mind when I glance at my bank account and calculate how much goes towards paying school loans.

—–

—–

Another colleague, after visiting the home of one of our faculty, remarked to me how humble her home was. This was despite the fact it was located in a well-to-do neighborhood and the obvious investment evidenced by the interior of the home. He wondered why a physician would choose to live in such a place, “unless she’s not really into money.”

I was not alarmed at his callous miscalculation; it’s incredibly common amongst the One Percent I will soon join.

Even now, when my salary is a little egg, waiting to hatch after a few more years of incubation, I can appreciate the gulf between the 99% and the 1% as it was laid out during the Occupy Movement. The “have-nots” will always want to be a “have”.

—–

—–

By the time my sojourn across the Midwest and East Coast landed me in nYc there had been rumbles of the approaching demise of the Occupy Movement. Story after story, video after video, documented how it had lost its initial intention, but I needed to see it for myself.

The evening I arrived I slept on the couch of some close friends. I awoke the next morning, jumped on the train and headed straight for Zuccotti Park.

I stormed up the subway stairs ready to embrace the chaos I had heard so much about, but it was gone.

All of it. In the midst of my previous day’s travels and late arrival, a plan had been put in place and executed to end Occupy Wall Street.

—–

—–

The end of a movement. The end of my curiosity? It all enhanced my desire to not be a member of the One Percent, despite a plotted collision course with exactly that mentality.