science

Allen Street

Author: Dr. Lewis Thomas (1913-1993)

Reprinted from “The Youngest Science: Notes of a Medicine Watcher”

Canto I: Prelude

Oh, Beacon Street is wide and neat, and open to the sky

Commonwealth exudes good health, and never knows a sigh

S collar Square, that lecher’s snare, is noisy but alive

While sin and domesticity are blend on Park Drive

And he who toils on Boylston Street will have another day

To pay his lease and live in peace, along the Riverway

A thoroughfare without a care is Cambridge Avenue,

Where ladies fair let down their hair, for passers-by to view

Some things are done on Huntington, no sailor would deny,

Which can’t be done on battleships, no matter how you try

Oh, many, many roads there are, that leap into the mind

(Like Sumner Tunnel, that monstrous funnel, impossible to find!)

And all are strange to ponder on, and beautiful to know,

And all are filled with living folk, who eat and breathe and grow.

Canto II

But let us speak of Allen Street—that strangest, darkest turn,

Which squats behind a hospital, mysterious and stern.

It lies within a silent place, with open arms it waits

For patients who aren’t leaving through the customary gates.

It concentrates on pending results, and caters to the guest

Who’s battled long with his disease, and come out second-best.

For in a well-run hospital, there’s no such thing as death.

There may be stoppage of the heart, and absence of the breath

But no one dies!

No patient tries this disrespectful feat.

He simply sighs, rolls up his eyes, and goes to Allen Street.

Whatever be his ailment—whate’er his sickness be,

From “Too, too, too much insulin” to “What’s this in his pee?”

From “Gastric growth,” “One lung (or both),” or “Question of Cirrhosis”

To “Exitus undiagnosed,” or “Generalized Necrosis”

He hides his head and leaves his bed, and, covered with a sheet,

He rolls through doors, down corridors, and goes to Allen Street.

And there he’ll find a refuge kind, a quiet sanctuary,

For Allen Street’s that final treat—the local mortuary.

Canto III

Oh, where is Mr. Murphy with his diabetic ulcer,

His orange-red precipitate and coronary?

Well, sir,

He’s gone to Allen Street.

And how is Mr. Gumbo with his touch of acid-fast,

His positive Babinskis, and his dark lunatic past?

And what about that lady who was lying in Bed 3,

Recently subjected to such skillful surgery?

And where are all the patients with the paroxysmal wheezes?

The tarry stools, ascitic pools, the livers like valises?

The jaundiced eyes, the fevered cries, and other nice diseases:

Go! Speak to them in soothing tones. We’ll put them on their feet!

We’ll try some other method, some newer way to treat

We’ll try colloidal manganese, a diathermy seat,

And intravenous buttermilk is very hard to beat

W’ll try a dye, a yellow dye, or different kinds of heat

But get them on their feet

We’ll find some way to treat

I’m very sorry, Doctor, but they’ve gone to Allen Street.

Canto IV

Little Mr. Gricco, lying on Ward E,

Used to have a rectum, just like you or me

Used to have a sphincter, ringed with little piles,

Used to sit at morning stool, face bewreathed with similes,

Used to fold his Transcript, wait in happy hush

For that minor ecstasy, the peristaltic rush…

But in the night, far out of sight, within his rectal stroma,

There grew a little nodule, a nasty carcinoma.

Oh, what lacks Mr. Gricco?—Why looks he incomplete?

What is this aching, yawning void in Mr. Gricco’s seat?

Who made this excavation? Who did this foulest deed?

Who dug this pit in which would fit a small velocipede?

What enterprising surgeon, with sterile spade and trowel,

Has seen some fault and made assault on Mr. Gricco’s bowel?

And what’s this small repulsive hole, which whistles like a flute?

Could this thing be colostomy—this shabby substitute?

Where is this patient’s other half! Where is this patient’s seat!

Why, Doctor, don’t you recollect: It’s gone to Allen Street.

Canto V: Footnote

At certain times one sometimes finds a patient in his bed,

Who limply lies with glassy eyes feeding in his head.

Who doesn’t seem to breathe at all, who doesn’t make a sound,

Whose temperature is seen to fall, whose pulse cannot be found.

And one would say, without delay, that this is a condition

Of general inactivity—a sort of inanition—

A quiet stage, a final page, a dream within the making,

A silence deep, an empty sleep without the fear of waking—

But no one states, or intimates, that maybe he’s expired,

For anyone can plainly see that he is simply tired.

It isn’t wise to analyze, to seek an explanation,

For this is just a new disease, of infinite duration.

But if you look within the book, upon his progress sheet,

You’ll find a sign within a line—“Discharged to Allen Street.”

The Death of Magneto

Magneto was beginning to feel a cool wave of energy course through him. So close as to almost be one with him, Dr. Bett calmly placed his left hand on Magneto’s shoulder and his right hand, with stethoscope resting in the palm, against Magneto’s chest.

As calmly as the placement of his hand, came the words from Dr. Bett’s mouth.

“Don’t be afraid. Don’t run away- stay where you are.”

Magneto, born from tireless experiences of Intern year, knew a last gasp struggle with Dr. Bett would be moot. The poison Dr. Bett had so effortlessly and stealthily placed on Magneto’s mucous membranes was already causing a microscopic cascade of cellular apoptosis.

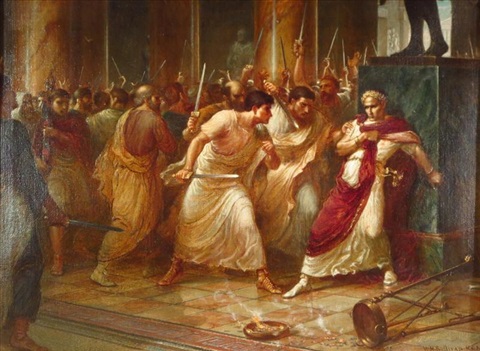

“Et tu, Dr. Bett?”

It was all Magneto could think to say in the moment before his death.

“Only Magneto had to die for this ambition,” responded Dr. Bett, recalling Brutus in the moments after he joined the assassination of Caesar.

Since his birth, Magneto had anticipated the greatest threat to his existence to come from his progenitor, Ean the Intern. From Ean’s grueling experience, Magneto had arisen as a counterbalance to the unbridled instincts and passion necessary for survival in Medical Residency.

Magneto had provided the organization and realization necessary to prevent Ean the Intern’s passions from destroying himself from within and ending this fantastic journey in its infancy.

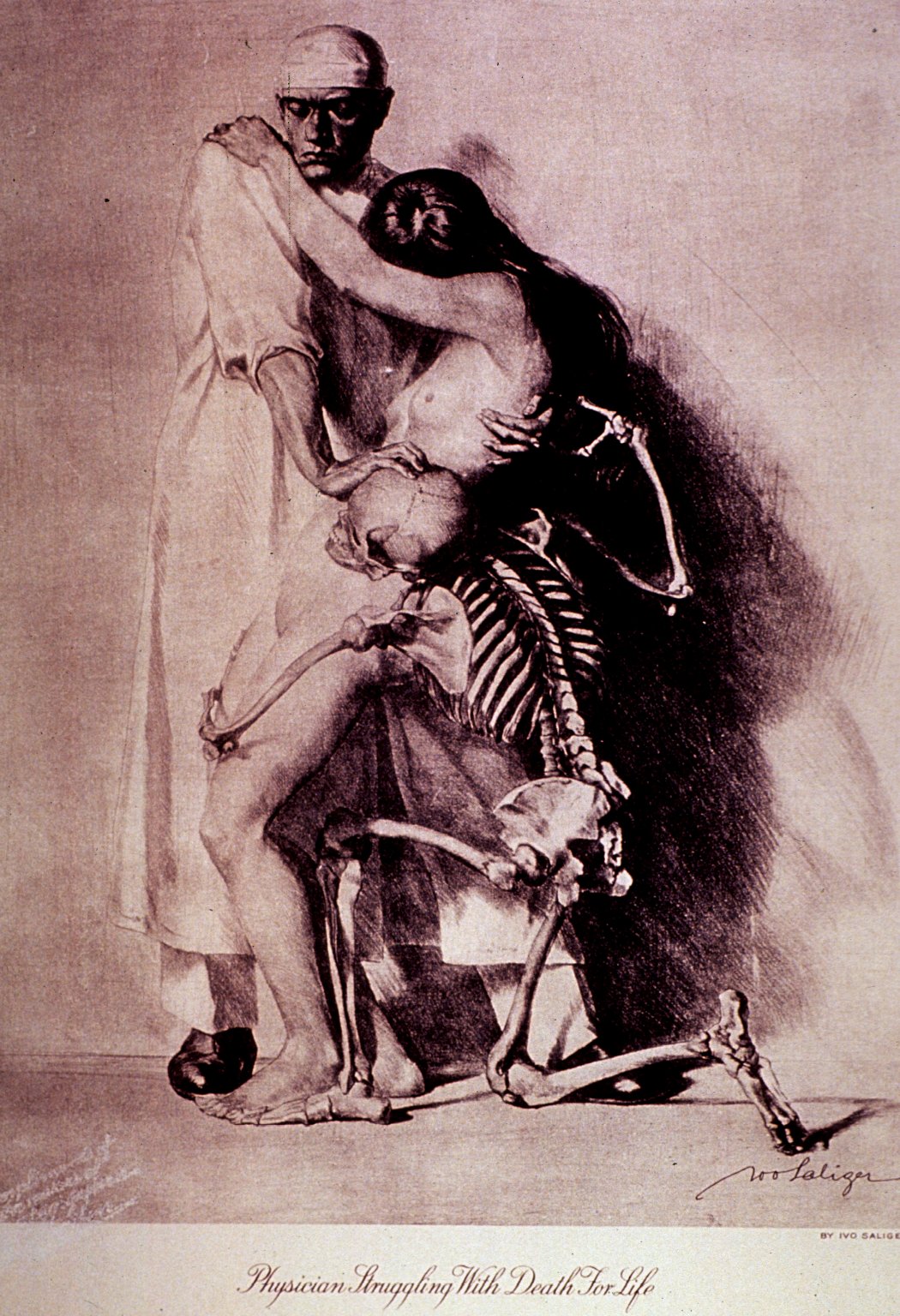

Inadvertently, Magneto became the genesis for the Super Ego, Dr. Bett, who would become the moral compass on their tenuous journey.

Having given rise to Dr. Bett, Magneto was astounded of his own capabilities, but even more so, he was in awe by the strides Dr. Bett had made.

Each step Dr. Bett had taken brought Ean and Magneto closer to their ultimate goal. It also provided them even greater strength. His passion increasing along every one of Dr. Bett’s strides, Ean became harder for Magneto to control.

Magneto’s sole purpose now seemed to revolve around keeping Ean’s passions in check and preventing them from obliterating their common purpose as the completion of Residency loomed ever closer.

Dr. Bett had entrusted this responsibility upon Magneto, from which he expected a long and successful existence.

His last moments, so close to the end of their journey, had not been anticipated.

As the end of Residency became a reality, Dr. Bett began to feel the weight of Ean and Magneto with each step he took. While both had been necessary for his own creation, he could not envision the next journey coming to fruition if he would have to be responsible for them both.

This misunderstanding, which blinded Dr. Bett ever increasingly, gave rise to The Death of Magneto.

While Ean could at times create trouble if not adequately balanced by Magneto, Dr. Bett believed Ean’s instincts to be invaluable to their next journey. Simultaneously, Magneto’s own strength, as a counterbalance and as his own entity, could not be overlooked.

Dr. Bett, after painful deliberation, could see Magneto becoming too powerful to control due to the opportunities awaiting them on their next journey. Eventually, Magneto’s strengths could make Dr. Bett unnecessary.

More importantly, Magneto’s relationship with Ean, while needed at this stage, was not deemed to be necessary by Dr. Bett in the future. Dr. Bett could harness Ean’s energy on his own.

And if Magneto eventually realized that Ean was beholden to him, and not Dr. Bett, it would be Magneto, and not Dr. Bett, who would truly be in charge of this journey.

This was a reality Dr. Bett was not willing to allow.

There was a brief moment when Magneto looked into Dr. Bett’s eyes as his vision blurred and the sound of his own heart faded.

Dr. Bett looked as caring and thoughtful as ever.

It was a moment not foreseen by Magneto. But he was comforted by it.

That was the moment. The Death of Magneto.

The World is Flat

Despite centuries of knowledge to the contrary, I’ve considered that Aristotle was wrong.

Or that Sir Isaac Newton didn’t know what he was talking about.

And maybe Eucledian geometry had a major flaw.

None of these amazing scientists or their eye-popping equations accounted for one significant variable: life in the 21st century.

We are living in an age of mankind which could not have been predicted, even by the most sophisticated understanding of the world in centuries past.

I can send a real-time message to a friend in India with imperceptible hesitation between communication devices.

I can watch video of the sun rising upon the Australian shore.

I can order a tool, have it manufactured in Germany, and delivered to my doorstep within a week.

I can view the image of an assassination in Turkey and almost instantaneously share my shock and awe with a colleague located only minutes from the dead body.

I can step foot in each of these countries with the push of a button.

When I left my home in Wichita, KS over 20 years ago, I couldn’t have imagined where my life would take me. At that moment, I was headed East, to Lexington, KY, to start anew after the divorce of my parents.

In the subsequent years, I developed a heightened awareness and independence I doubt few expected. Eventually, those traits carried me even further East to Boston when I was 24; an effort to figure out what I would make of my life immediately ensued.

I took my first step on foreign soil in 2005; I had not yet read Thomas Friedman’s 21st Century Economic Bible, “The World is Flat”, but in a cosmic moment of clarity, I inherently knew my life had been forever changed.

At my brother’s behest, I began reading Friedman’s account of how modern life and technologic advances had defied the laws of physics set forth by nature and confirmed by some of the greatest scientists to ever walk the Earth.

Ten years have passed since I finished Friedman’s manifesto. And my thirst for global excursions has yet to be satiated. Each time I have traveled abroad for pleasure was akin to another sliver of my brain being turned on for the first time.

When I lived abroad for two years during medical school, on a small, moderately inhabited island in the Caribbean, I had the opportunity to see how the world could still be flat, in ways Friedman never expounded upon.

The simplicity, beauty, and innocence of Dominica were unmistakeable at times. But in the next instant, I’d be immersed in the medical knowledge accumulated over the course of millions of hours of scientific discovery. The juxtaposition was remarkable.

I readily acknowledge: I have lived a charmed life; one full of opportunities I have been thankful for; as well as those I’ve created for myself.

Each success has been no small feat. Many were met with significant resistance. Some with initial failure.

But I have been persistent. Persistent in my desire to prove Friedman correct. Persistent in my desire to meld the scientific truths of Aristotle, Newton, and Euclid with the economic realities of modern life.

I only know one way of doing this. To travel. To find the experiences that allow us to come as close to surreal as possible. I crave them.

The World is Flat.