Where the Heart is

Kristi called out to me in a soft whimper, “Ean?”

I responded by peering up the stairway to the third floor, whereupon I could see her right hand grasping her left wrist. Blood was visibly seeping out between her fingers.

It was Martin Luther King Jr Day. The year was 2007. And at that point, I had been living in a group home for 2 and a half years.

I had arrived home a few moments earlier, ascended the stairs to the second floor, and set my bag down outside of the small staff office. It would remain there until I returned home from the Emergency Department by myself several hours later.

Kristi heard the front door close all the way from the third floor. Perhaps her senses were exponentially heightened due to the shock of seeing blood spray from her wrist as it was sliced by a razor. Her next instinct had been to leap from her bed and into the hallway. She could only see my shoes from her vantage point to the second floor, but even such a minute bit of information gave me away.

Kristi’s decision to end her life had coincided perfectly with my return home from a peaceful day off.

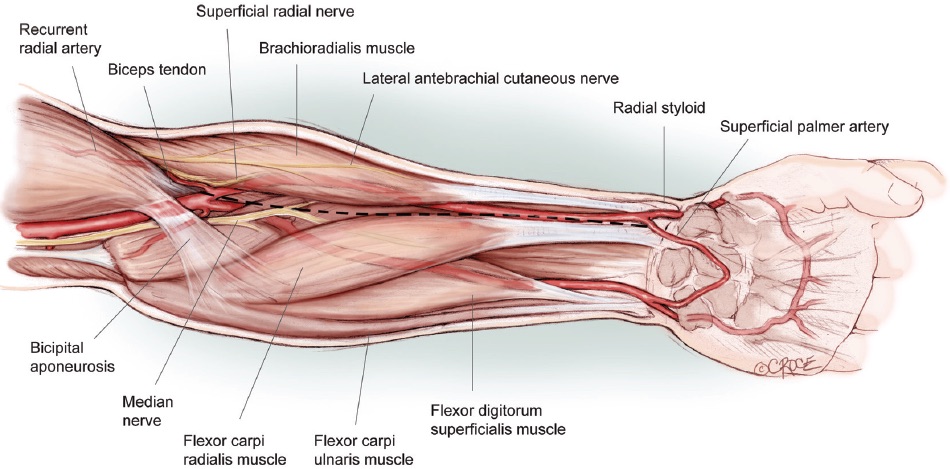

I quickly scampered up the stairs as Kristi stood outside her bedroom. I unlocked the door to my own bedroom, which was located caddy-corner to hers and grabbed a towel. Kristi was half-sobbing, half-whimpering as I pressed the dark blue hand towel on top of her right hand. Standing outside her room, I could tell that she had been seated on her bed when the razor punctured her radial artery; a fine spray of red blood was juxtaposed against the yellow wall.

She pulled her right hand from below the towel so I could apply even more direct pressure. After a moment, she made a fist and flexed at the wrist as I took a quick peek at the damage. The pressure kept more blood from squirting out, but I could tell we needed to head to the nearby Emergency Department immediately. Kristi resisted my initial suggestion to go to the hospital, but after a moment of thought, she could see the concern in my face, as well as the blood on her right hand and now the towel and agreed to go.

I knocked on one of the other staff’s bedroom door, located directly across the hall from Kristi’s, hoping she was home. Thankfully, she was. I gave her a quick synopsis of what happened and asked her to clean the wall with some bleach before Kristi’s roommate returned.

The Cambridge City Hospital was only one street over from our home, a social project developed by Harvard psychology graduate students over forty years earlier. Our close proximity meant we were in the ED only five minutes after Kristi retrieved a razor blade. Once there, Kristi was apologizing profusely every few seconds for ruining my towel; its dark blue color disguised the carnage beneath.

The ED was not particularly busy, especially for a holiday, but I didn’t like the idea of sitting in the waiting room any longer than necessary. Though the bleeding had almost completely subsided, my rudimentary medical knowledge in those days told me this was due mostly to the flexion of her wrist and the pressure it was causing.

However, I could not help but visualize Kristi extending her wrist and spraying blood on the backs of the family sitting in front of us. So I went up to the triage nurse and politely explained that my friend’s injury was self-inflicted and would she please move us to the front of the line so she could be evaluated.

Through the glass partition, the nurse looked out into the waiting room and saw Kristi sitting there, holding the towel against her flexed wrist and nodded at me. I called to Kristi and she stood up, took a few steps towards the door separating the waiting room from the triage bay, and grimaced.

Only fifteen minutes earlier, as I had been walking home from the YMCA in Central Square, Kristi had been on the phone talking to her older brother, who happened to be a physician. Despite his training as a psychiatrist, he had not sugar-coated his concerns about her mental health when he informed her that he didn’t feel safe leaving her alone with his young son during an up-coming visit. She began crying and hung up the phone.

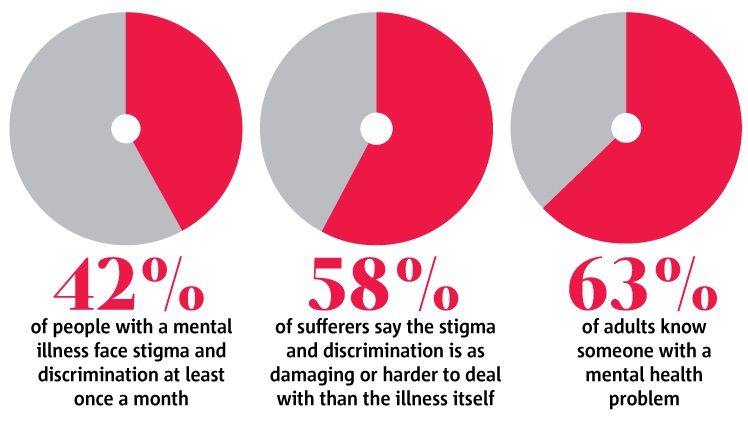

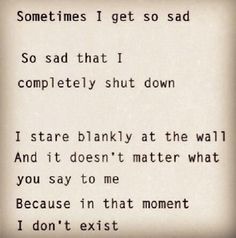

Despite Kristi’s battle with depression in her early twenties, she had graduated from law school and begun a successful professional career. But as it does with so many individuals, depression seeped back into her life and had become all-encompassing. A suicide attempt led to a hospitalization for several weeks at one of the world renowned psychiatric hospitals in Boston.

Upon her discharge in the fall of 2006, she joined our group home after a week-long communal interview process that was required for all residents and staff. The first few months had been difficult for Kristi, due to her inability to find a steady job in the legal field again. When a reliable temp position opened up a few weeks earlier, she began to thrive.

But that call, and the message therein, drew out her self-hatred and the fury of “helplessness and hopelessness” which characterizes depression. Unbeknownst to myself and the other staff, who lived in the home with the residents, Kristi had been prepared for this desperate last act. When she returned from the Emergency Department several hours after I had departed, she asked me to remove the box of razor blades hidden in one of her drawers.

Over the course of three years, I lived in two group homes belonging to the same organization in Cambridge, MA; first as a counselor, then as the director of the home where I lived with Kristi. Focused on helping high-functioning individuals transition from in-patient hospitalization (for mental health issues) back to independent living, the opportunity to be a part of this unique program had brought me to Cambridge from Ohio in my pursuit of becoming a clinical psychologist.

But in the fall of 2004, after only a few short months of living in one of the homes and participating in the project as a counselor for its residents, my purpose in life was irrevocably transformed. I had come to get hands-on experience by living within the mental health population, learning how to best serve their health needs, but I was shocked to see how pathetic the basic medical care is within this portion of our community; a chance encounter with another young professional who was going back to school to become a physician set my wheels in motion.

The three years I spent living with over 60 incredible people, those who were trying to conquer their illness and others like myself who wanted to help, transformed my life and gave me the strength and perspective to survive my own trials and tribulations.

My experience as a medical student, my failures and successes therein, the friends I made, the colleagues I cherished, the patients I cared about and for… all of them were a direct result of my life in a group home.

Home. Truly, where the heart is.