Gray’s Anatomy

—–

The most prominent book on my mantle is Gray’s Anatomy, a text I received from a colleague with whom I worked at Man’s Greatest Hospital. After many hours spent working side-by-side in the Gastrointestinal Cancer Center, she felt it was a fitting gift as I embarked on my mission to becoming a physician.

Nearly six years later, I’m an Intern in a Family Medicine residency program, trying to learn how to become the quintessential doctor.

—–

—–

I spent the first six months of Residency filling many different roles, each of them markedly different from the one before or after. I have been an Internist, Clinician, Gynecologist, Primary Care Provider, Nocturnist, Infectious Disease specialist, Pediatrician, Teacher, Obstetrician, Podiatrist, and Trauma Surgeon. I have also become an even bigger fan of sleep than I ever could have imagined.

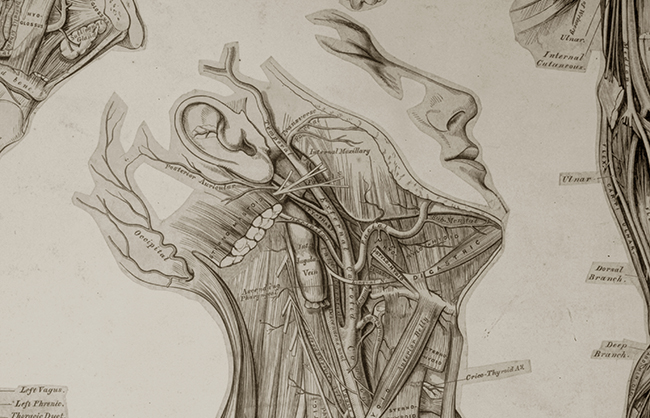

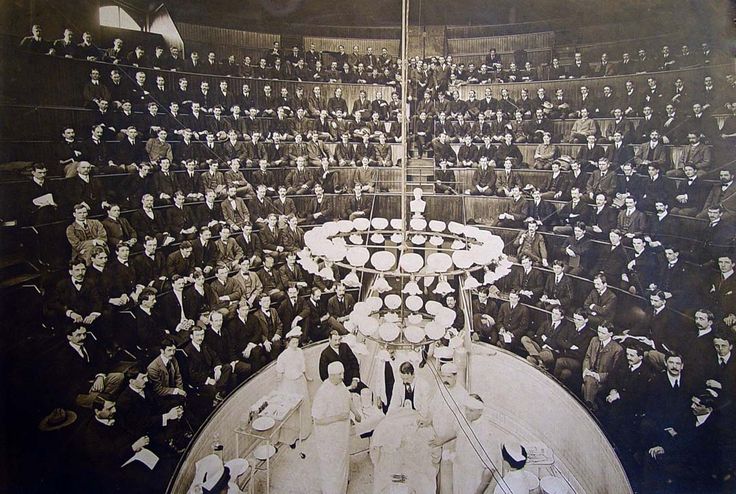

The copy of Gray’s Anatomy which I received is a facsimile of the 1901 version, the 15th edition of Henry Gray’s medical masterpiece of the human body. Not much has changed in human biology in the past 113 years, but Gray’s experiences as a physician and lecturer at the Royal College of Surgeons is probably somewhat different from what I experienced in the past six months… or perhaps not.

—–

—–

Day 1 of Residency I was assigned to our Internal Medicine service, responsible for running around the hospital admitting patients, providing them care, discharging them home, all while hoping I’d done a serviceable enough job teaching them about their medical ailment to prevent a hasty return to the Emergency Department.

Of the services we staff as Residents (service = four-week stint as a physician of a specific branch of medicine), Internal Medicine at my Residency is the most labor intensive, sleep-depriving, nerve-wracking, hair-splitting service of them all. The official name is Clinical Medicine, or Clin Med for short (or Clin Dred when you know the next four weeks are about to evaporate into the ether).

—–

—–

Somehow I became one of the two “lucky” lottery winners to be a first-year Resident assigned to Clin Med. My partner was a friend from medical school whom I had known since the beginning. We were paired with two senior Residents, who ostensibly had been the highest functioning first-year Residents on the Clin Med service the previous year and were thus chosen to be our medical mentors.

The ensuing four weeks were so busy that I spoke to my friend for exactly 8 minutes and 11 seconds during the entire month (that includes the time it took to type text messages).

I was told being chosen to start on the Clin Med service should be considered an honor… basically meaning that during my time as a student at the same program the previous year, they had come to the conclusion I would not be responsible for the early demise of any patients who would be placed under my care.

—–

—–

I thought it comparable to being told I would be allowed to be the first person to jump out of an airplane without a

parachute. Low and behold, not a single patient died under my care; or really had any significant downturn in their medical malady.

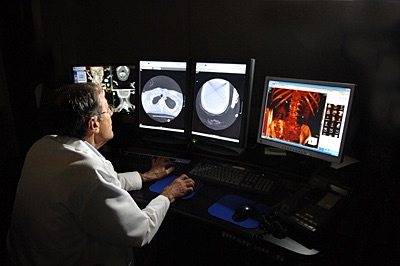

The days were filled with trying to learn how to navigate the choppy waters of a medical institution and its systems, and the computer programs which allowed me to chart on my patients, along with a physician’s responsibility of percussing my patients’ backs, feeling for pedal pulses, listening to a heart beat while gently pressing along a radial artery, writing perpetually changing orders, and allowing for my own bodily functions to occur when I had a moment.

—–

—–

At the end of the month, I took a deep breath, realized I had survived my first service as a Resident, glanced at the

Gray’s sitting on my mantle, and wondered aloud, “what the hell just happened.”

—–

After a month of learning on the fly about how to be a functional physician in a fast-paced hospital environment, the following two weeks were a nice respite, a smattering of out-patient visits to social service providers in Columbus, office visits by established patients in our out-patient office… and a couple of shifts in the Gyn Clinic.

My experience as a medical student during the six week rotation of Obstetrics and Gynecology were by far the worst of my clinical training. I only survived it by forming a bond with two other colleagues who were equally averse to the responsibilities therein. After that rotation I spent the next two weeks traversing around the Eastern half of the US, visiting old friends, drinking away the memories on an adventure I called “The Journey to Reclaim My Soul.” Sticking a speculum, or even worse, my sterile-gloved fingers, inside women I had met only moments prior wasn’t exactly why I had decided to become a physician.

Stepping foot inside the Gyn clinic was a bit of a flash-back to days of yore. Days I would rather forget. But, I chose to become a Family Medicine physician because I wanted to experience a full-scope of practice, so I needed to use those memories to help the new women I would have asking me about their privates.

—–

—–

In the midst of those two weeks, there were a smattering of half-days in the office, where patients would come to their appointment expecting to see me; not some doctor who happened to be available. They had formally been told I would be their physician. It was a bit of a culture shock unlike what I experienced on the In-Patient service, where people arrived in the hospital hoping for someone with a medical background to cure their ails.

This time, they were expecting “Dr. B.” Whether or not they liked me or thought I was helpful would determine if they would think of me as “Dr. Bullshit” or “Dr. Badass.”

Two short weeks of community clinic visits, office appointments, and speculum insertions were followed by flipping my schedule and going on night-call for two weeks.

It evoked memories of my life for the six months prior to Residency, when I had worked overnight; Except I was traversing the ED, the emotional rollercoaster of my equally sleep-deprived senior Resident, and the perils of septic shocks and intubations at 3am, rather than deciding which return bin to toss some junk into at Amazon.

—–

—–

It had not started smoothly, as my transition back to nocturnal life stymied my brain’s ability to function on the level necessary for a physician. By the end of the second night (by night I mean at 6am, 12 hours into our shift), my senior Resident, 9 years my junior in age, and I had a tit-for-tat critique of each others performance.

—–

—–

And when I say “tit-for-tat” and “each others”, I mean, I got my ass handed to me and had to sit there and take it like a man. By the end of those two weeks though, he and I were having a nice breakfast reminiscing about all the crap we had successfully lived through together.

Gray certainly didn’t write anything about that in his book; I checked.

—–

The first two months of Residency seemed to last forever, but at the same time, it seemed to be over before I knew it. The next two months were spent down the street at the nationally recognized Children’s Hospital, where it is customary for the Interns of my Residency to spend back-to-back months there learning the medical art of Pediatrics.

—–

—–

I was only starting to get the hang of being a Resident by that time, making the transition a bit of a shock to the system as I needed to learn all new faces and an all new electronic medical record; all while assimilating to the hierarchy of a whole new medical specialty.

The Residents of Children’s Hospital learn the ins and outs of treating babies, children, adolescents, teenagers, and the occasional grown adult still suffering from their pediatric medical maladies… I needed to become one of them quickly. The assimilation process when you are a physician is expected to occur over the course of a couple of hours; not a few days or weeks.

So of course I started on the Infectious Disease service right as a never-before experienced scourge affectionately known as “Asthmageddon” swept the Midwest.

—–

—–

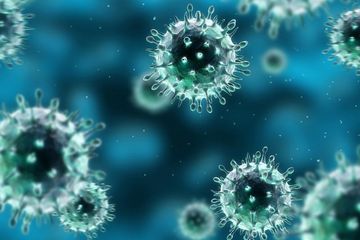

Asthmagedden was a region-wide exposure to a newly recognized virus, Enterovirus D68, which was causing babies and children of all ages, with and without previous asthma afflictions, to show up in the Emergency Department in Status Asthmaticus, a diagnosis indicating the inability of the respiratory tract to respond to front-line medical therapy, causing a constant difficulty in breathing.

http://www.wcpo.com/news/health/healthy-living/watch-respiratory-illness-ev-d68-found-in-ohio

Enterovirus typically affects the gastrointestinal tract, causing horrible diarrhea and concomitant dehydration, but as evolution has shown us, a few changes to a gene here or there and all of a sudden a new Enterovirus emerges, now equipped to attack the lower respiratory tract.

Children who had never wheezed, the most common sign of asthma, were having their bronchi inflamed by the virus, making it difficult for air to pass. As somebody who grew up with asthma, I can attest that this is a terrifying feeling.

—–

—–

Some of these children were so sick they were immediately admitted to the Intensive Care Unit to receive the most minute-by-minute care to assure they would not suffocate from a blocked airway. These critically sick children by-passed our normal Infectious Disease unit, but as their symptoms resolved, they would be shuttled to our unit to continue their care alongside the children who were not as severely afflicted.

Of course, a Pediatrics Infectious Disease unit is also full of little tykes with butt abscesses, whooping-cough, diarrheal illnesses, crusty eyes, and non-remitting otitis media (ear infections); and a whole host of anxious parents, who typically become the biggest concern of Residents.

After seeing all of this, I’m re-thinking my plan of having children one day, if at least so I don’t need any psychotropic medications when my kids get sick.

—–

—–

The first three services were a whirlwind of cognitive adventure, psychological daring, and physical extremes. When I hung up my scrubs on the last day of Pediatric Infectious Disease, it was with the knowledge I was only a quarter of the way through Intern Year.